Last week I wrote a post about some of the aspects of development besides economic growth that policy makers should take into account when dealing with the developing world, and today I would like to continue in a similar vein. This time, however, I am going to discuss a different variable: culture.

Over the summer I read a book called The Sex Lives of Cannibals, which sounds racy but is in fact very entertaining (and informative) travelogue by J. Maarten Troost. Troost and his girlfriend move from D.C. to the Tarawa atoll in Kiribati (Kir-ee-bas), a small, impoverished South Pacific nation few have ever heard of. His girlfriend spends her days working as director of an NGO, while Troost explores the island and documents what he learns about the people and the culture.

small, impoverished South Pacific nation few have ever heard of. His girlfriend spends her days working as director of an NGO, while Troost explores the island and documents what he learns about the people and the culture.

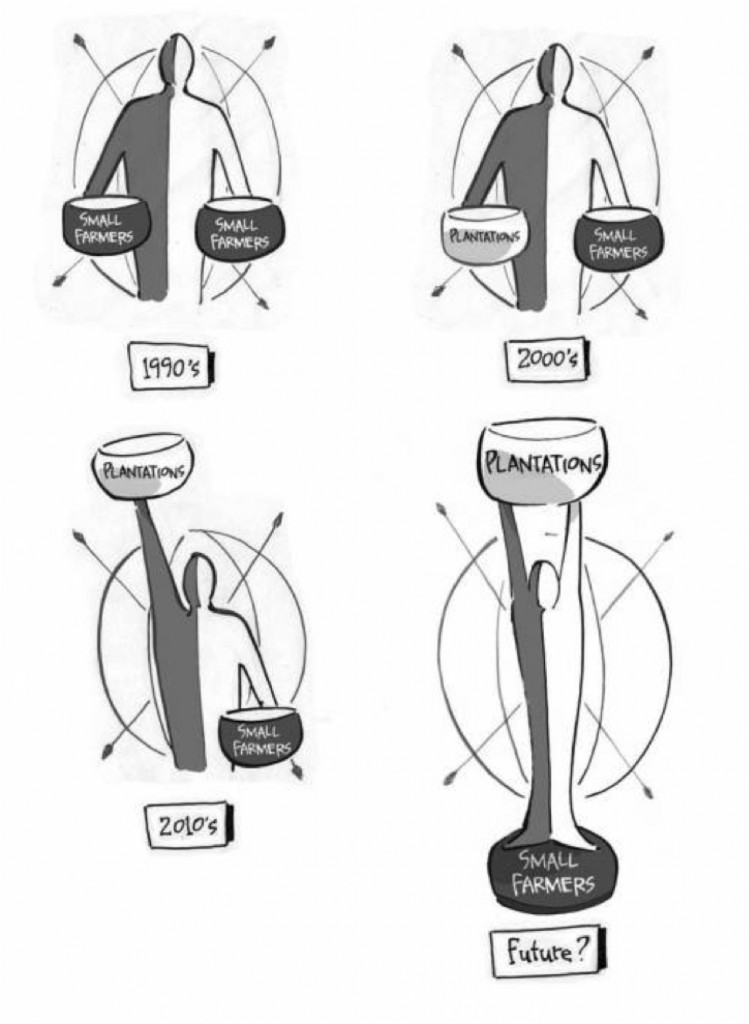

One of the things I found particularly interesting about this book was Troost’s description of the Bubuti system. Under the bubuti system, someone can come up to you and say “I bubuti you for your fishing net,” and you are obliged to hand it over without complaint. The next day, you can go to the one who took your fishing net and say, “I bubuti you for your shoes,” and he will have to hand them over to you. It’s a way that the society on the islands remains egalitarian, and it’s also the reason why the I-Kiribati (the people of Kiribati) avoid positions of power.

Troost relates the story of a well-educated young I-Kiribati who was in line to become the manager of the Bank of Kiribati but who begged his superiors not to promote him. He explained that if he were to be promoted people would come to him and bubuti him for money and jobs, and so the Bank remained in Western hands. The bubuti system is also the reason why Troost’s girlfriend was able to get a job as director the NGO. Previous NGO’s had attempted to turn control over to the I-Kiribati, but as soon as they did so bubuti requests ate up their budgets and they were forced to dissolve. I-Matangs (westerners) are outside the bubuti system, and so are able to have powerful positions without the whole organization crashing down around them.

Now, I find this very interesting, since one of my interests (and focus areas for research) is international economic development. As a westerner, I tend to focus on job creation and its relationship to economic growth, but clearly there can be contradictory forces at work. In a place like Kiribati job creation is not necessarily linked to economic development, and giving the local people positions of power within the organizations that were created to help them—usually a positive and sustainable way to encourage development—only causes those organizations to crumble. Culture is always something that needs to be taken into consideration when trying to foster international economic growth, but I think this example really emphasizes the extent to which culture plays a role. Obviously it’s an extreme, but surely there are other places where similar systems can be found. Policy makers and aid organizations need to be sure to take these things into consideration.

always something that needs to be taken into consideration when trying to foster international economic growth, but I think this example really emphasizes the extent to which culture plays a role. Obviously it’s an extreme, but surely there are other places where similar systems can be found. Policy makers and aid organizations need to be sure to take these things into consideration.

Of course it’s nice to say that culture needs to be taken into consideration when dealing with economic development, but how do you do that? How do you deal with the bubuti system? It’s certainly an interesting question. The system seems designed to prevent people from gaining too much wealth, and it deters people from seeking positions of power. So how to you create a practical, sustainable organization that encourages economic growth and works with (or around) the bubuti system? Any suggestions?

Michelle Bovée is a SISGI Group Program and Research Intern focused on international affairs, economic development, and responsible tourism. To learn more about the SISGI Group visit www.sisgigroup.org