In my last post I discussed Green Mountain Coffee and their use of Fair Trade products in their mission towards sustainability. While only mentioning it in passing, I grew curious about what Fair Trade truly means. I imagined that any organization with such lofty goals and altruistic means must inevitably have a controversial side as well. Similarly this being Fair Trade month, I thought I would present the debates surrounding the movement.

In the mission statement of Fair Trade USA, they claim the desire to foster a trade model that promotes empowerment, sustainability, and equity from the ground to the consumer. They state:

We envision Fair Trade as a new global business model that helps industry secure its own profitability and competitiveness while it protects the environment and ensures a fair return to farmers and workers. We help industry forge long-term partnerships throughout the supply chain so companies can both obtain the highest quality products and support disadvantaged producer communities.

These goals seem ideal for any socially responsible business to promote. Where can people possibly stand to criticize? Well, apparently the arguments fall into a few categories: price distortion and mainstreaming.

When examining price distortion, the argument goes that this business model only works on a small scale. This means that although Fair Trade seems to be everywhere, it only encompasses a small percent of total global agriculture. If Fair Trade grew to work with more farmers, these farmers will expect the higher wages that will eventually raise the price of the commodity. This is troubling for two reasons. First, it encourages other regional farmers to plant that crop thinking they too will get a good price. This eventually oversupplies the market as well as limits the staple crops being produced for the region. The second trouble behind expected higher wages is non-Fair Trade farmers are being hurt by the prices increase. In risking a price collapse, these farmers will be in an even worse position than before Fair Trade came to the market. Price distortion is a strong case against Fair Trade. However they have countered this reaction by promoting crop diversification into less crowded sectors, which means they are still promoting responsible agriculture but not risking flooding the markets with a single good.

The criticism of mainstreaming is based on the fear that the farmers on the ground are not the ones necessarily receiving the better prices for their better practices. In 2006, French Economist Christian Jacquiau reported “There are only 54 inspectors around the world, working on a part-time freelance basis to check and control a million producers. These checks do not take place on the ground but in offices, hotel rooms or even by fax.” Examinations show that there is little monitoring or follow up studies after partnerships are started. Therefore there is little evidence that impacts are even being seen.

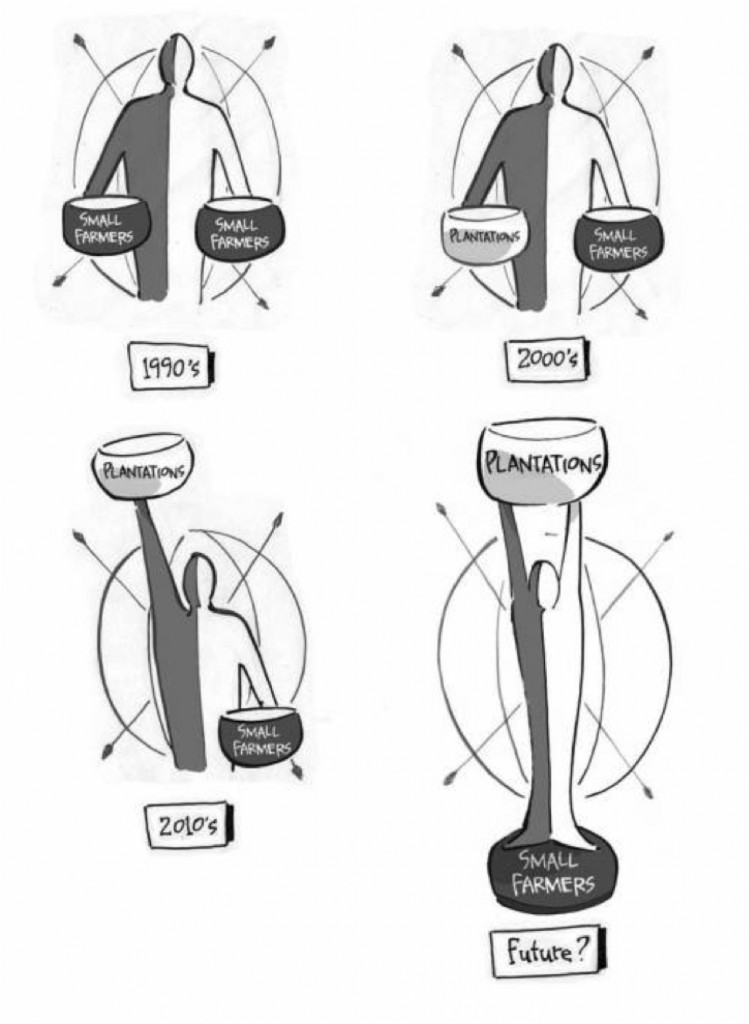

Mainstreaming more directly refers to the criticism that Fair Trade is working within current economic frameworks, as opposed to creating a new system. I can best explain this through the response that is being taken to recognize this. CLAC (The Latin American and Caribbean Network of Small Fair Trade Producers) is working to unite small farming organizations for facing the international arena. While this was Fair Trade’s initial mission, it has since become a promoter for plantations, no longer working with small individual farms. The global risk of this is it leaves behind individual farmers because they have no competitive chance against large-scale plantations. CLAC essentially wishes to create an alternative trade system, one outside the current unregulated system that is in place today. They believe, as Fair Trade once did, that empowering the individual farmer with a voice does the greatest good for strengthening the farming communities.

Essentially these arguments show that the small-scale market that Fair Trade has cornered has been successful in placating the Western concern for equality and development. However, this business plan will not be the panacea for the future that many consumers believe they are purchasing towards. I think that our first step towards a solution is to buy locally and scale down our consumerist tendencies; but I recognize that this is already a lot to ask.

Also, notice that the labels “organic” have not been discussed once. I hope that consumers do not mistake the label of Fair Trade with “organic”. Where organic products are sometimes Fair Trade, not all products with Fair Trade stamps are necessarily organic. I fear that well-intentioned consumers are potentially blindsided in trying to remember what environmentally-sustainably produced-fair priced-products are available and best to buy. I must confess, that I read more into this topic because I was one of these consumers.

I don’t wish to criticize this movement in an attempt to deter consumers from purchasing these products. I do however, wish to bring to light that where intentions are often good, we must continually seek accountability and proof that our actions and funds are going where they claim.

–Katherine Peterson is a Program and Research Intern with the SISGI Group focused on theories of development, globalization, and political ramifications of development work.