A recent study conducted by the University of California in Los Angeles revealed some interesting results for children between the ages of nine and eleven. The study polled young children between the given age group, and asked them to rank values that are important to them. Out of all the values that the tweens could have chosen, “fame” came shining through at number one. Other important values that came in as the top most contenders were physical fitness and monetary success. On the other hand, community service and volunteer work were ranked rather low, and did not appear to be of much concern to the children.

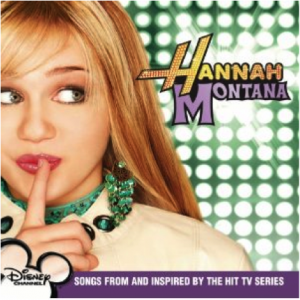

What has happened between 1997 (when kids in a similar study ranked “fame” as fifteenth on their list of important values) and 2011? According to UCLA’s study, the yearning for fame and financial success is a product of the television shows, commercials, and movies tweens watch. Tweens are one of the most highly targeted audience members for television executives, and an entire media empire has been dedicated to them. Shows like “Hannah Montana” and “iCarly” depict fairly young kids skyrocketing to stardom through singing, acting, or internet blogging. Internet sensations turned into mega superstars, like Justin Bieber, also give off the impression that fame is the ultimate goal that tweens should aspire to attain.

audience members for television executives, and an entire media empire has been dedicated to them. Shows like “Hannah Montana” and “iCarly” depict fairly young kids skyrocketing to stardom through singing, acting, or internet blogging. Internet sensations turned into mega superstars, like Justin Bieber, also give off the impression that fame is the ultimate goal that tweens should aspire to attain.

Unfortunately, this means that young children are clearly losing sight of the importance of family, friends, and a good education. According to Patricia Greenfield, co-author of the study and Ph.D from the Department of Pyschology at UCLA, “Tweens are unrealistic about what they have to do to become famous. They may give up on actually preparing for careers and realistic goals.” Statements such as these are extremely problematic in today’s world because they indicate that there is a lack of understanding on the part of young children. Instead of focusing on becoming doctors, teachers, lawyers, and establishing strong bonds between friends and family, tweens are looking for the quick fix to super stardom.

As alarming as the news is, the blame cannot completely fall on the shoulders of these star struck tweens. Television shows, movies, parents, and communities themselves need to help children become in tune with truly important values like volunteer work and community service. Furthermore, as difficult as it may be, it is important to get children involved in activities other than watching television or using the computer to watch TV. It is imperative to remember that tweens will one day be the future of America, and they cannot be concerned about only fame, money, and physical beauty.

If you are interested in learning more about issues affecting the youth under the age of 25, the SISGI Group’s Alliance for Positive Youth Development will be hosting a webinar on Wednesday, August 31st. The “State of Youth-Issues Impacting Youth Under 25” webinar will be from 2-3 pmEST, and will be an excellent opportunity to learn what issues are impacting youth the most. To register for the webinar, simply go here, and follow APYD @ideas4youth on twitter or like us on Facebook to learn more about APYD’s youth initiative.