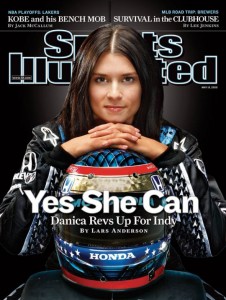

Marketers have realized that it’s easy to sell the blonde, a.k.a. Maria Sharapova (the highest paid female athlete in the world for the past eight years) and the beautiful, a.k.a. Danica Patrick (Yahoo’s most searched athlete, male or female last year). It’s Marketing 101. Beauty sells.

Marketers have realized that it’s easy to sell the blonde, a.k.a. Maria Sharapova (the highest paid female athlete in the world for the past eight years) and the beautiful, a.k.a. Danica Patrick (Yahoo’s most searched athlete, male or female last year). It’s Marketing 101. Beauty sells.

Do a quick Google search of “most famous female athletes” and the third highest hit is “Sex Sells: Female Athletes Who Know How to Market Themselves”. The fourth hit? “100 Hottest Female Athletes of All Time”. Not exactly what I mean by “famous”, but it’s the sad truth. Sex appeal sells, especially when it comes to female athletes. In the words of sports industry consultant, Marc Ganis, “never underestimate the importance of physical beauty to an athlete’s endorsement opportunities”.

It’s also easy to sell female athletes who are defined by their role in the family. Everybody loves to see athletes in the role of “loyal girlfriend” or “loving mother”. Society accepts such marketing because it fits in with traditional gender roles. It allows athletes to show their softer side, and allows them to be defined by their femininity first, and their athleticism second.

However, what can marketers do for those not considered particularly “feminine”? For the ones considered to be “tomboys” or “manly”, or even just those who possess particularly male characteristics, like aggressiveness and strength? How to deal with those athletes, who might be among the best of the world, yet don’t fit in with the traditional gender roles?

It all comes down to marketability; Americans won’t forget you if a company can sell you. But four decades since Title IX and 16 years since the launch of the WNBA, organizations are still figuring out how to attract consumers by marketing female pro athletes, especially those who might not conform to traditional notions of femininity. -Fortune Magazine

Case in point: Remember the story about U.S. weightlifter, Sarah Robles? How she was ranked as the best American woman in the super heavyweight division coming into the Olympics, but was barely getting by financially due to a lack of endorsements and her general anonymity in the sporting world? Robles had to depend on a $400 monthly stipend from U.S.A. Weightlifting, along with help from her family, friends, and food pantries just to get by. The problem was that she didn’t fit the stereotype – she wasn’t a size two athlete, with blonde hair and blue eyes. She didn’t fit the mold. And therefore, she didn’t get the endorsement deals. While Robles is an extreme case, she highlights the dilemma that many female athletes face. How does one promote oneself when one isn’t able to “fit the mold”? Female athletes in all types of sports are dealing with the fact that success on the field doesn’t necessarily translate to success from a marketing standpoint.

Something I do like? Advertising campaigns like Nike’s “Voices” commercial this summer, which highlights the novel idea that women can indeed be athletes. Same goes for a Gatorade ad campaign introduced earlier this year, featuring soccer player Abby Wambach. In the commercial, Wambach is not framed as highly sexualized, or even particularly feminine – she’s simply portrayed as a fierce competitor. A refreshing take on the typical role of female athletes in advertising. Of course, it’s important to note that the majority of Gatorade’s executives are female. Funny how that works out.