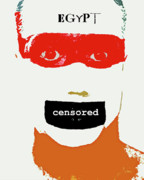

It has been quite a year for censorship in the Middle East. The crackdown by Egyptian regime officials and their security apparatuses on protestors’ communications was relentless, going so far as to completely suspend cell phone and Internet service for up to a week at a time. During a revolution, half an hour without cell or Internet coverage

Poster Available for Purchase online -http://fineartamerica.com/featured/egypt-censored-no-1-chad-miller.html

could be devastating, let alone seven days. It’s remarkable how far the demonstrators were able to go considering their lack of technological resources.

It was only a matter of time before these practices of massive censorship were truly drawn into question. At the time the networks were suspended, protestors and their sympathizers were outraged, unquestionably leading some to double their resolve in demanding regime change. But only now are we beginning to see how the new temporary Egyptian leadership will respond to what former Egyptian President Mubarak and Co. did while in office.

One small yet necessary measure undertaken by the Egyptian Ministry of Communications and Information Technology has been to pay local phone operators for losses incurred as a result of the government shutdown. Though some have complained that the amounts the ministry intends on dolling out are far from adequate, this measure at least demonstrates that the current leaders are willing to address the problem head on rather than attempting to downplay or ignore the mistakes made by the previous regime. This is a welcome and refreshing change to a corrupt political system that has failed to address certain concerns of its citizens for decades.

But paying out sums of money doesn’t fix the problem; it only dampens the outcry against past mistakes. The censoring of calls made on Skype, an Internet phone service, is still proving to be contentious. Many Egyptians, and people around the world for that matter, were under the impression that Skype calls and chats were far more secure than other methods of communication. It’s true that Skype does make things especially difficult to censor, seeing as how it’s based entirely on a peer-to-peer network and uses incredibly sophisticated encryption. Even so, this level of user protection didn’t stop Egypt’s Electronic Penetration Department from allegedly intercepting calls amongst revolutionary activists. When protestors crashed their way into Egyptian state security headquarters, they found transcripts of their private conversations and a memo outlining Skype as the choice communication platform of extremist groups.

This begs the question: at what point has censorship gone too far? As I see it, censorship is a rabbit hole – once you start it, it’s hard to stop. For example, say the Egyptian security forces had collected information concerning the leader of a group of violent protestors. If honest, legal methods didn’t reveal this person’s identity, hacking into private Skype conversations amongst dissidents might, especially if their superiors were hounding them to produce results. Even though they were violating basic rights of privacy, the twisted mindset tells them that they are doing it for the greater good.

Obviously, this is a dangerous and immoral train of thought. I imagine that now that the practices of Egyptian security are publically being drawn into question, some of its employees are wondering why they ever probed so deeply and dishonestly to begin with. They dove into the rabbit hole, or perhaps it was their superiors who shoved them in, and before long it was too late to crawl out.

This is not an argument that takes into account the semantics of Egyptian pre and post revolutionary law – I don’t know what their constitution states about censorship. My point is that whomever ends up leading the state after upcoming elections must make it known to the Egyptian people that they will guard the administration from infringing as far into privacy rights as Mubarak did.

Perhaps even Mubarak never intended to push so far into the private lives of Egyptians. It’s easy to demonize him now that the revolution is complete and to assume that leaders of other nations around the world would act more responsibly in the face of an uprising. Unfortunately, the rabbit hole is universal. This should be a wake up call to any nation that’s pushing the limit on censorship within the confines of their own laws – if you keep digging deeper and deeper, you may never find your way out.

Ryan Pavel is a Program and Research Intern with the SISGI Group focusing on foreign military involvement, policy and strategy into conflicts and motivations behind and impact of foreign aid. To learn more about the SISGI Group visit www.sisgigroup.org