Southern Sudan’s wildlife could provide it with an opportunity to develop a vibrant tourism industry

July 9th is fast approaching. This is the day when south Sudan is scheduled to secede from the north and become an independent nation – something many of us have been eagerly waiting for. Violence has plagued the build up to this monumental day, but a recent agreement between northern and southern Sudanese military forces to withdraw from the disputed oil-rich regions offers a glimmer of hope that the south can separate in relative peace.

But what happens when the south does secede? How can a brand new poverty stricken nation build itself into a more economically sound nation? One helping factor, as I’ve discussed before, is the role played by aid organizations. Another factor is the assistance offered by foreign nations who have an interest in helping south Sudan get to its feet. This aid will probably be particularly generous when coming from the nations that rely on Sudan’s vast oil reserves, such as China.

To an extent, both of these factors neglect to take into account what the Sudanese themselves can do to help lift their nation out of poverty. So what does southern Sudan have to offer outside of oil?

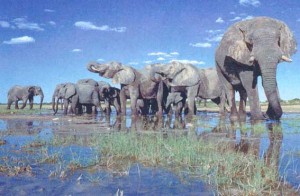

Despite years of war and unkempt hunting, Sudan still has an incredible amount of wildlife. In recent aerial surveys, as many as 1 million antelopes, 300,000 gazelles and 5,000 elephants were counted as they roamed across the plains. The lack of an established tourism industry means that there has been little incentive to foster the growth of these animal populations. Why bother regulating them if no one is coming to see them anyway? It also means that there are few measures in place to discourage poaching. In one national park in the south that spans 10,000 square miles, there are only 150 park rangers – that’s over 66 square miles per ranger.

established tourism industry means that there has been little incentive to foster the growth of these animal populations. Why bother regulating them if no one is coming to see them anyway? It also means that there are few measures in place to discourage poaching. In one national park in the south that spans 10,000 square miles, there are only 150 park rangers – that’s over 66 square miles per ranger.

Some tour providers in neighboring countries have already jumped on the idea of expanding the industry to south Sudan. While assistance from those experienced with the running of such an industry should be welcome, the southern Sudanese are the ones who need to end up managing it. Otherwise, any capital raised might slip right out of south Sudan and defeat the purpose of creating the industry to support the new nation all together. Members of the Wildlife Conservation Society who are already working in Sudan alongside the Sudanese could help train more locals on how to care for the wildlife and help the number of animals to grow. Without the animals, after all, there is no safari adventure.

It’s clear that the desire for a more tourist friendly nation exists, as some groups have already signed up for Sudanese safaris that don’t yet exist. The innovators and some adventurous tourists are there, but the actual program is not.

When people think of the African continent, many think safari. While safari may not be inherently connected to Sudan as it is to, say, Kenya, with the right amount of animal protection, tourism promotion and security enhancement, Sudan could attract a vibrant crowd of adventure tourists. The value of attracting this crowd extends beyond that of the money charged for the actual event. Foreigners need a hotel to stay in before and after the safari, they need food to eat and they need transportation. All of this helps put money in the local pocket. Even if the safaris are package deals run by foreign companies, the industry would give southern Sudan an opportunity to shine as a place that is worth visiting – and revisiting.

I am not so naïve as to believe that a robust tourism industry alone could prop up southern Sudan economically, but I do think that it could make an important contribution. Anything that could help shift southern Sudan from a poisonous reliance on oil should be welcome. The southern government should of course focus on building better infrastructure to help address the basic needs of its citizens, but it should also focus on projects that could help the country in the long term. As for the latter, managing the wildlife might just be the ticket.

Ryan Pavel is a Program and Research Intern with the SISGI Group focusing on foreign military involvement, policy and strategy into conflicts and motivations behind and impact of foreign aid. To learn more about the SISGI Group visit www.sisgigroup.org