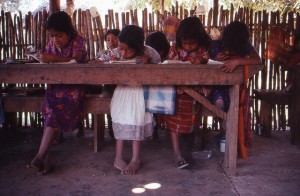

It’s that time of year again: back to school. Parents and kids all over the US are preparing for another school year. And what do they do to prepare? Buy snazzy new clothes to impress their friends and classmates, stock up on binders and pencils, and wind down summer activities like camp and family vacations. It’s a privilege to be able to do all of these things because for many refugee children (and adults) in camps around the world school and all the trappings that go along with it are not an option.

It’s that time of year again: back to school. Parents and kids all over the US are preparing for another school year. And what do they do to prepare? Buy snazzy new clothes to impress their friends and classmates, stock up on binders and pencils, and wind down summer activities like camp and family vacations. It’s a privilege to be able to do all of these things because for many refugee children (and adults) in camps around the world school and all the trappings that go along with it are not an option.

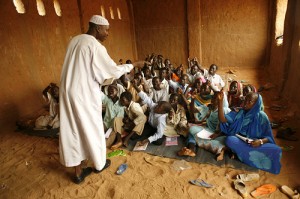

Education has been identified by the UN as a fundamental human right that is crucial to the development and wellbeing of the individual. But, for refugees who have fled conflict, natural disasters, poverty, or environmental crises for the (supposed) safety of a camp, education can only be considered a luxury. Now this general statement definitely doesn’t apply across the board to all refugee camps. The 2011 UNHCR report ‘Refugee Education: A Global Review’ shows the variability of children’s educational enrollment rates in refugee camps ranges from 0-100%. This discrepancy points to how some camps like those reported in Pakistan offer no education while in other camps, like some in Chad, every refugee has access. You can’t get a bigger gap than that, now can you? So, some kids luck out and some don’t. That’s just not fair.

Access to education in camps varies camp to camp, country to country and depending on the humanitarian organization running the operation. This  in and of itself makes it difficult to create some sort of guarantee through standardization that all refugee camps provide education to all refugees that want it. As does the fact that refugee camps are known for lacking such basic necessities such as: food shortages and malnutrition, lack of water, poor sanitation and adequate housing. When camps are struggling against hunger, disease and dehydration; how can you expect for them to bother worrying about the other basic human right, education, that won’t immediately kill refugees if they go without? Education is long-term and must be built up over time, whereas basic survival must be met short-term to avoid dire consequences.

in and of itself makes it difficult to create some sort of guarantee through standardization that all refugee camps provide education to all refugees that want it. As does the fact that refugee camps are known for lacking such basic necessities such as: food shortages and malnutrition, lack of water, poor sanitation and adequate housing. When camps are struggling against hunger, disease and dehydration; how can you expect for them to bother worrying about the other basic human right, education, that won’t immediately kill refugees if they go without? Education is long-term and must be built up over time, whereas basic survival must be met short-term to avoid dire consequences.

So, how do refugee camps provide adequate education for hundreds to tens of thousands of refugees all at different levels of education? That’s a HUGE and complex question to take on. It requires dealing with logistics, funding and resources; and without one component none of it will work. Ideally all camps would be able to provide, culturally appropriate curriculum would need to be developed, and testing would need to be available to place refugee at an appropriate educational-level given their previous education.

Then there’s the issue of human resources: who will develop the curriculum and where do teachers come from, the host country or humanitarian organization? Host countries may not have the desire or resources to spare for camps and humanitarian organizations are often already so strapped for money to even provide the most basic necessities, that they may not have the money to hire teachers or buy educational materials. Ideally, they would be able to rely on volunteers coming in to teach, but there would no doubt be some training involved that would cost money. This kind of work asks a lot of volunteers and it I doubt there would be enough volunteers to fill the need. Perhaps developed countries could sponsor teachers to teach in refugee camps.

What would be great would be to compile a best practices list of refugee camp education programs that have worked, that are cost-effective and low resource, and could be adapted. Perhaps an Advisory Board, say with the refugee experts at the UNHCR, could be created to assist organizations running camps in adapting these best practices to their situations, leveraging their resources. However, given that there are 42 million displaced people around the world and thousands of refugee camps, assembling these best practices would be no small feat. It would require collaborative efforts between both local refugee organizations with much experience working on the ground and larger refugee organizations experienced in researching and evaluating refugee camps. UNHCR would be ideal for conducting this research given their experience in refugee research and wide network of partnerships with local, national and international nongovernmental organizations.

What would be great would be to compile a best practices list of refugee camp education programs that have worked, that are cost-effective and low resource, and could be adapted. Perhaps an Advisory Board, say with the refugee experts at the UNHCR, could be created to assist organizations running camps in adapting these best practices to their situations, leveraging their resources. However, given that there are 42 million displaced people around the world and thousands of refugee camps, assembling these best practices would be no small feat. It would require collaborative efforts between both local refugee organizations with much experience working on the ground and larger refugee organizations experienced in researching and evaluating refugee camps. UNHCR would be ideal for conducting this research given their experience in refugee research and wide network of partnerships with local, national and international nongovernmental organizations.

Can you think of any good examples of refugee camp education programs that have worked and would be considered a best practice? How did they deal with issues of funding and providing enough resources to ensure education was adequate? Are they adaptable to other countries and cultures?

1 pings