The narrative that the coronavirus does not discriminate based on race, gender, or class is a false concept that needs to be addressed. While in theory, yes, the coronavirus does not discriminate, our systems do. A year into the pandemic, the coronavirus has deepened the consequences of pre-existing inequalities that are placed on BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color). As environmental justice professor Julie Sze mentions in her book, Environmental in the Moment of Danger, in moments of catastrophe, pre-existing social, racial, and economic inequalities and disparities among marginalized communities are exacerbated. Similarly, marginalized communities have always faced acute challenges and barriers prior to the pandemic, but COVID-19 has only worsened them.

As most of us know, poverty and racism are intertwined. As both of these categories play off of each other, they can influence a wide range of quality of life and personhood outcomes. Here are a few factors that can heighten COVID-19 risks among the BIPOC community.

1. Occupation

1. Occupation

Occupation plays a major role in the disparities of the coronavirus, as people of color are disproportionately represented in “essential” hospitality jobs. These work settings include healthcare facilities, grocery and convenience stores, factories, public transportation, and farms. Not only are these positions low paying, but people who work in these sectors are most likely to catch the virus because of constant exposure. Not to mention, essential workers are also less likely to own a car, especially in large metropolitan cities. The coronavirus pandemic puts low-income essential workers, who depend on public transportation to go to work, at high risk. White-collar workers have the privileges of working from home, therefore are less likely to contract the virus. This suggests that being able to stay home during the pandemic is a luxury. One of the best ways to avoid getting the virus is to social distance and limit contact with others, but because hospitality and low-income workers have no choice but to move around in order to make ends meet, close contact is inevitable.

2. Inadequate Access to Healthcare

2. Inadequate Access to Healthcare

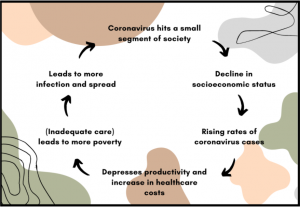

As mentioned above, people of color are often victims of classism and are disproportionately represented in low-paying jobs compared to their white counterparts. These jobs are also often exploitative, meaning that any sudden illness could cost them their job or without paid leave. The main problem is the U.S. healthcare system. It’s profit-driven and built for the elite, despite the most vulnerable people who are heightening their risks by going to work every day in order to pay their bills and are without healthcare. Without the proper care, they could have a major impact on the broader society as well. If one person can not get the proper treatment, that person poses a risk to others, especially if you live with other family members or in densely populated areas. To break it down, by not providing adequate access to healthcare, it’ll just produce the same outcome over and over again. It’s a vicious cycle.

3. Housing Conditions/Location

3. Housing Conditions/Location

Race and class are major contributors to health disparities and complications. Residential segregation between Black and white Americans still remains, which perpetuates major wealth and opportunity gaps. Therefore coronavirus rates can vary vastly from neighborhood to neighborhood. Racial and ethnic communities are often located in densely populated buildings and neighborhoods or have multi-generation households. Sharing a household or living in proximity to neighbors puts them at greater risk compared to those living in single-family homes.

Food Apartheid

Food Apartheid

Food insufficiency is no question how COVID-19 has impacted the BIPOC community. There are major parallels to food insecurity and housing location among low-income people of color. A lot of low-income neighborhoods with communities of color have limited grocery stores offering healthy choices at an affordable price and limited transportation to take them to get groceries. Low and inadequate access to healthy food can increase the risk of obesity and heart disease as people living in food deserts will more likely opt for low-priced meals at local fast-food restaurants. Underlying health conditions that are associated with food inaccessibility, COVID-19 deaths are bound to have a devastating impact on BIPOC who live in food deserts. Although the coronavirus has had negative economic impacts in wealthy neighborhoods too, it’s tougher for pre-existing vulnerable communities to afford fresh, healthy fruits and vegetables which are more expensive than processed foods.

4. Pre-existing Health Conditions

4. Pre-existing Health Conditions

Similarly, pre-existing health conditions also highlight the disproportionate effects of COVID-19. Low-income BIPOC communities are also often located near LULUs (locally unwanted land use) because it’s more affordable. In fact, according to the UCC report, race is the number one indicator of whether you live near a toxic waste facility. As mentioned, living situations and housing can make someone more susceptible to the virus. Our health is determined by social and economic conditions and physical settings, such as exposure to toxins that affect water and air quality. In this case, living in close proximity to hazardous waste facilities can heighten their risk of getting covid because they already had respiratory-related health issues, such as asthma, from living in polluted neighborhoods.

Every aspect of the pandemic, race, socioeconomic status, privilege, etc…, exposes the not-so-hidden inequalities of America that people of color have faced for centuries. It’s important to understand that these racial disparities are no accident and that the structural positions of marginalized communities are not different outside the COVID-19 pandemic. These devastating disparities put on low-income people of color have always existed within our nation’s systems through historical and everyday practices. We are seeing how systems slip into their violent behavioral patterns and how these issues have become institutionalized. These inequalities highlight the urge for systemic change, and as the pandemic continues, we see this virus is no equalizer of race.

Overused phrases such as “we are in this together” to show solidarity in regards to those affected by the pandemic don’t acknowledge the disparities of the coronavirus. Everyone is dealing with the pandemic in their own way, and some worse than others. For some, the coronavirus may not have affected them in the slightest, and some may not feel a sense of togetherness within the broader societies. “We’ll get back to normal soon” also disregards the pre-existing inequalities the coronavirus has amplified. “Going back to normal” means continuing racist patterns in which the BIPOC community faces the burdens of capitalist inequality. These phrases are meaningless when applying to all of society as it does not account for people who have been most affected, before, during, and after the pandemic.

Not only has the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected the BIPOC community due to systemic inequalities, but many have also faced personal obstacles. Caring for dependents and other family members can put a lot of stress on caretakers, especially while dealing with other struggles and trying to stay afloat. I had the privilege of interviewing Tirhas, a Black immigrant and single mother from Eritrea, to share her story about the hardships she has faced during the pandemic.

Has your life changed since the pandemic? If so, how?

“I have lost a lot of social connections. There were a lot of community gatherings and getting together, which was not allowed. I also was very active in my church, but my church had to follow pandemic restrictions. I was also very worried about my child. My child is only nine years old, and when she switched to online learning, I’ve expressed how stressful my child might learn. I don’t know how many nine-year-olds can sit for 7 hours at a computer and knock all this work out. It’s almost impossible and unrealistic, especially when there are no classmates, no friends, and no recess. It’s not easy for the both of us.”

What was it like caring for your dependent during the pandemic?

“It’s been hard. It’s been really hard. Like many single moms, when the pandemic hit, schools out. School is like daycare for most moms. When I drop my child off, she is in school for 6 to 7 hours, and it gives me time to go to work. When there is no school, what are all these single mothers supposed to do with their children? I was fortunate enough to have a family friend to look after my kid, so I was able to come to work. But making sure my daughter is all set up for remote learning was a struggle. I don’t know much English, so making sure she got a computer, understanding the schedule, and other things that had to go before my daughter was ready for remote learning was a stressful situation while also trying to juggle work.”

There is also disproportionate vaccine access among the BIPOC community. While inadequate access to the vaccine and lack of resources may play a major role, this pandemic also has shown how the BIPOC community feels about taking the vaccine. By using moments of history as precedent, the modus operandi of the government has been to experiment on people of color.

Were there any emotional struggles or barriers you faced during the pandemic?

“Yes. So many of my friends and colleagues have been trying to convince me to get the vaccine, but I’ve always been afraid. Seattle is very culturally diverse, and from what I’ve heard, I’m not the only one who is afraid to take it. There is a reason why some people in the African American community are afraid to take the shot because in the past, we have been used as guinea pigs. There has been an inheritance of mistrust from the government because my ancestors, my community, were used as guinea pigs. Like the Tuskegee study, where African men were asked to participate in this scientific experiment on syphilis that was conducted by the US Public Health Services. These participants were not aware they were being infected with syphilis but were told they were receiving treatment for bad blood. When this study was initiated, there was no treatment for the disease, so they used Black American males as experiments to observe what syphilis is like untreated. Dozens of these men died because they had no idea and were not told about the research.

These conspiracy theories have felt very real to me, but these feelings are not validated by white, educated Americans. Many times the governments of the world have proven themselves to not be worthy of trust, so why would that make it unreal? Just like how Black people see the criminal justice system as corrupt or how the government doesn’t care about the disproportionate violence we face from the police… Now all of sudden, they are telling us to take the vaccine. It doesn’t make sense.”

It’s no surprise that vaccine hesitancy is rooted in mistrust and doubts. It’s not an irrational fear or about misinformation, but rather awareness of centuries of being mistreated by the government.

To help combat hesitancy and doubt, we need to be more empathic about these feelings, explain diversity in the vaccine trials, or have people who look like the community members give the vaccine. By validating the real history and experienced-based reasons why the Black community is afraid to take the vaccine, we can create common ground. Without understanding the history, we can’t empathize, and we can’t fix the problem with no empathy.