A few weeks back I went to a Garmeen Creative Lab Workshop, where Bill Moggridge, the Director of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum spoke about the new exhibition: Design With the Other 90% Cities. I was reminded of this exhibit when I was researching for my last piece on the 7 billionth person entering the world. The role of this Cooper-Hewitt event is to bring to the attention the expanding role and necessity of proactive design geared towards improving the lives of the growing number of people.

This brings me back to the fundamental question of how our planet is going to develop to sustain all of these humans. An emerging focus of development now is urban sustainability. Urbanization and the solutions that must follow are going to be a crucial focus for our future. As of 2008, the UN reported that more than half of the world’s population was living in urban cities and towns. In theory this should be a good thing. This puts less strain on governments, making education and health services more efficient and accessible to greater numbers. Similarly, closer proximity lends itself to ease in business and access to goods, while alleviating strain on surrounding natural biodiversity.

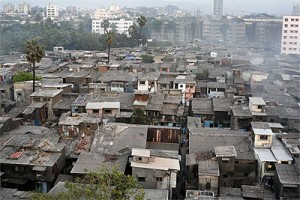

However, this is how things operate in theory. Reality shows that a number of cities are migration destinations leading to more rapid expansion rates than others. This is inevitably going to cause developmental constraints, often resulting in the formation of favelas, townships, slums, and informal housing settlements. It is easy to name such cities: Mumbai, Rio De Janeiro, Dhaka, ect. The question for the future is how do we learn from their solutions (failed or otherwise)? After all, these cities will be leading the example of how we approach and avoid such problems into the future.

inevitably going to cause developmental constraints, often resulting in the formation of favelas, townships, slums, and informal housing settlements. It is easy to name such cities: Mumbai, Rio De Janeiro, Dhaka, ect. The question for the future is how do we learn from their solutions (failed or otherwise)? After all, these cities will be leading the example of how we approach and avoid such problems into the future.

Through reading and actually having traveled through a number of townships myself, there appears to be a number of different approaches towards appeasing the settlers. However, I must ask if the theory behind each is sustainable.

Small scale, local projects such as the one in Cairo, Egypt have sprung up out of innovation. A pro-poor system of waste management was developed to send individuals door to door to collect and recycle waste. This provides income for both the collectors as well as alleviating the internal need to import certain goods by recycling 80% of the collected waste. A local need was observed and addressed in such an innovative way that the community directly benefits as well as the workers.

Other, more government promoted projects can be observed as well. In Thailand, the government has worked with the motorbike taxi drivers in unionizing the drivers and offering them a uniform. While this legitimizes their businesses, it also stands to serve as a platform for empowerment within the slum community. I am more prone to these types of projects because it would appear to bring a more steady income to a family, and brings recognition to a trade.

My fundamental issue with both solution is that they do not seem to inherently deal with the problem in a preemptive way. There are thousands of each of the aforementioned type of projects in place already (find more at Slum Dwellers International), but are they truly addressing the problems? Can we simply rely on these small-scale solutions for our future? I argue that the major migration capitals of the world need to fundamentally shift the focus of how they will progress into sustainability.

I know that it is impossible to start from scratch in creating infrastructure and reorienting development, but we must start making changes immediately. I believe that the issues we face with urbanization are nearly on the same scale as environmental conservation. We can no longer turn a blind eye towards these areas in the hopes that they are moved or become self-reliant and invisible.

One quote that put this into perspective is by Cynthia E. Smith:

Establishing thriving, sustainable cities in the Global North as well as in the Global South is imperative during this period of urban migration, climate change and economic expansion. We need to show a new generation of practitioners how to design for density and social inclusion through mixed-income cohabitation, long-term investment in multimodal public transportation, and collaborative regional approaches. We can all learn a great deal from developing and emerging economies about how to create innovative solutions with limited resources and challenging environmental requirements.

Coincidentally, Ms. Smith is a curator for the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. After reading her essay on urbanization, I hope to make it to the UN building and see the exhibit. After all, it will be the same one that national politicians who have influence over these decisions will be walking past every day. I suppose I just want to make sure it is convincing enough.

–Katherine Peterson is a Program and Research Intern with the SISGI Group focused on theories of development, globalization, and political ramifications of development work.