August 2021 marks the return to school for the majority of students across the U.S. For most school districts, this means in-person learning, and for some, this will be their first offline learning experience in 18 months. The progress in protections from COVID-19 through vaccines, social distancing measures, and other safety protocols has recently been tainted by the Delta variant. The introduction of a traditional school schedule sparks both anxiety and excitement for many. With this in mind, it’s important to remember that youth need support to make a successful transition into the new “normal.”

Childhood poverty, food insecurity, and housing insecurity have increased since the start of the pandemic. These barriers increase stress levels and vulnerability to negative physical, emotional, and psychological symptoms. Gen-Z ( currently ages 13-23) has been significantly impacted by the uncertainty, negativity, social isolation, and wide-scale changes brought on by the pandemic. 46% report worsening mental health since the pandemic started, which is a full 13% higher than any other age group. Recent data shows households with children are twice as likely to experience food insecurity, with 14% of all American households with children lacking enough to eat. These statistics are even higher for People of Color, with 19% of multiracial households, 17% of Black households, 16% of Latinx households, 7% of white households, and 5% of Asian households lacking adequate food supplies.

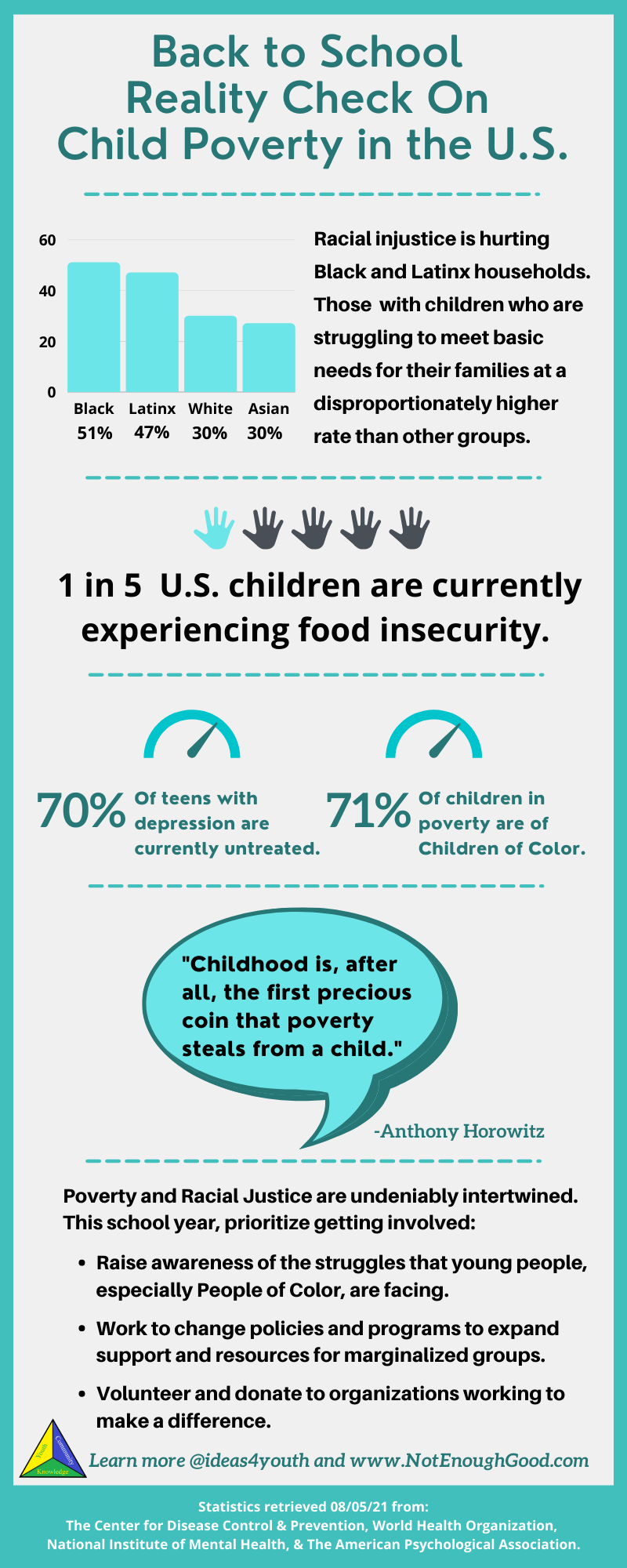

Meeting basic needs is a challenge for many households experiencing poverty, especially for those with dependents. According to CDC data from last month, a shocking 51% of Black households, 47% of Latinx households, 30% of white households, and 27% of Asian households with children report struggling to provide for basic necessities for their families in the past month. Rent payments continue to be a struggle, with 21% of households with children reporting being behind on their rent payments, compared to 12% of households without children. This places families experiencing poverty at an increased risk for homelessness, especially with the recent expiration of the Federal Moratorium on Evictions. While the CDC has decided after a lapse to continue the moratorium in “places with a significant transmission rate of COVID-19… expected to cover approximately 90% of renters” it is only until October 2021, and no longer covers all renters. This is a key example of how policy and policymakers directly influence the lives and well-being of young people.

Meeting basic needs is a challenge for many households experiencing poverty, especially for those with dependents. According to CDC data from last month, a shocking 51% of Black households, 47% of Latinx households, 30% of white households, and 27% of Asian households with children report struggling to provide for basic necessities for their families in the past month. Rent payments continue to be a struggle, with 21% of households with children reporting being behind on their rent payments, compared to 12% of households without children. This places families experiencing poverty at an increased risk for homelessness, especially with the recent expiration of the Federal Moratorium on Evictions. While the CDC has decided after a lapse to continue the moratorium in “places with a significant transmission rate of COVID-19… expected to cover approximately 90% of renters” it is only until October 2021, and no longer covers all renters. This is a key example of how policy and policymakers directly influence the lives and well-being of young people.

These statistics are a wake-up call that despite efforts such as stimulus payments to support youth and combat the negative impacts of the pandemic, there is still a great deal of work to be done. Here are key things to keep in mind while supporting youth in their return to school this fall.

1: Mental Health Matters

1: Mental Health Matters

- Encourage young people to express their thoughts and feelings in safe and appropriate ways.

- Help them explore and utilize a variety of coping strategies to manage their stress.

- Combat stigmas surrounding mental health with frequent and honest discussions.

- Refer to school-based or local mental health resources when possible for additional support.

2: Utilize Resources

2: Utilize Resources

- Remember that transportation barriers, lack of privacy, limited laundry facilities, and unreliable internet access are just a few of the barriers experienced by many students struggling with poverty. Be empathetic and understanding.

- Keep information on resources available to your community to share with students and families. In California, you can start here.

- Make sure the young people in your life know about free emergency mental health options such as Crisis Text Line. Text “HOME” to 741-741 24/7 for confidential mental health support via text messaging.

- Educate young people on their rights. Young people experiencing homelessness may be afraid to ask for help for fear of being prevented from attending school if they now reside out of the district. Education can open doors for youth to utilize the resources available and receive the support they need.

3: Promote Self-Care

3: Promote Self-Care

- Getting enough quality sleep is an essential part of being prepared for educational success. Talk with the young people in your life about the physical and emotional benefits of healthy sleep habits and how to combat barriers to quality sleep.

- Young people have reported significant stress, isolation, and unwanted weight gain since the pandemic. It’s important to foster a positive view of self as a foundation for self-care. Promote self-compassion, empathy, and a growth mindset through activities like this.

- Compile a list of positive self-care ideas that youth feel might help support them. Encourage the daily practice of at least one self-care skill and model these skills for any young people in your household. Some ideas to start that conversation can be found here, but feel free to utilize any positive activities that promote stress reduction and positive self-esteem.

4: Get Involved

4: Get Involved

- Donate your time or finances to organizations that support young People of Color and young people experiencing poverty and homelessness. These can be local food banks, shelters, internship and leadership programs for young people, afterschool programs, and other resources.

- Vote. One of the most significant ways to help young people is to vote in your local, state, and federal elections for candidates who prioritize racial justice and positive systemic changes. You can find out how to register in your state here.

- Monitor pending legislation. The Federal Eviction Moratorium is just one example of legislation that has major impacts nationwide. In California, a current bill with the potential to bring meaningful changes is the California Racial Justice for All Act: AB 256. This legislation is a continuation of 2020’s California Racial Justice Act: AB 2542 that prevents racial discrimination in future cases but is not retroactive. AB 256 would provide a legal way for people convicted of a crime based on racial stereotypes or racist statements made by anyone involved in the criminal investigation or court proceedings the right to a new racially unbiased trial. Contact your policymakers to express your support for legislation that promotes racial and social justice in your area.

5: Promote Accountability

5: Promote Accountability

- Challenge yourself to practice self-examination of implicit and explicit biases, actions, and attitudes that could hinder or hurt others. Apply a racial justice lens in everyday life, especially when working with young people. A recording of our most recent youth development conference and other educational resources to promote growth and best practices can be found here.

- Hold each other accountable and have those tough conversations when someone does or says something they shouldn’t. Resources to help you in tough workplace conversations can be found here.

This back-to-school season will be different than any other, but it also has the potential to usher in many positive changes. Together, the youth in our communities can feel supported and rejuvenated. There may still be lingering uncertainties, but one unwavering reality is that regardless of the unexpected changes, we will continue to adapt and support youth and each other.

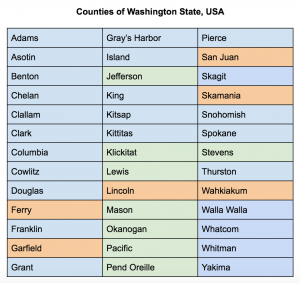

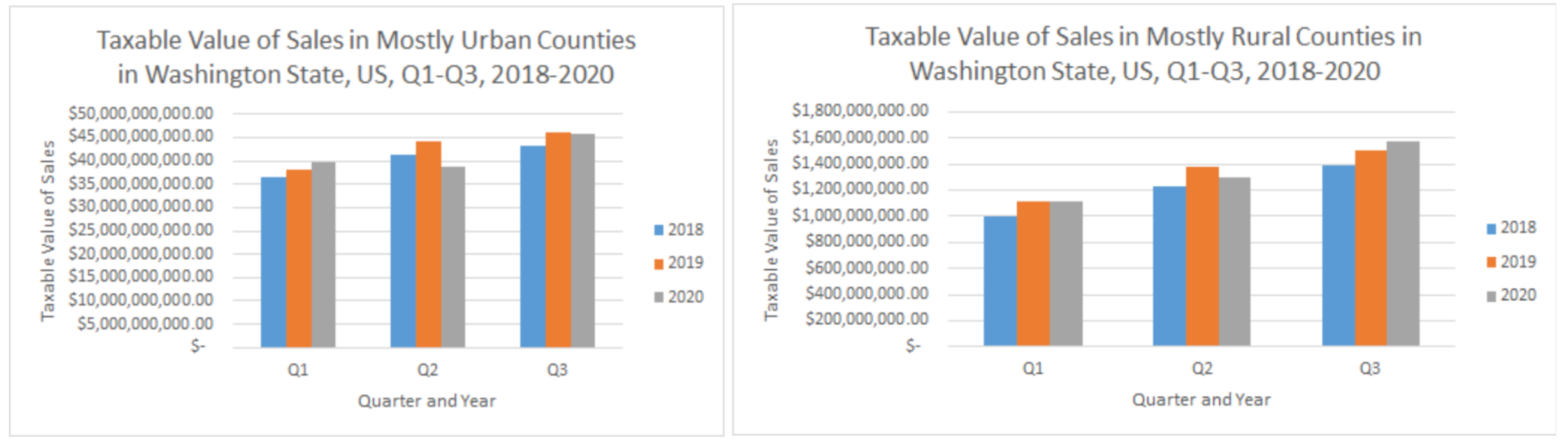

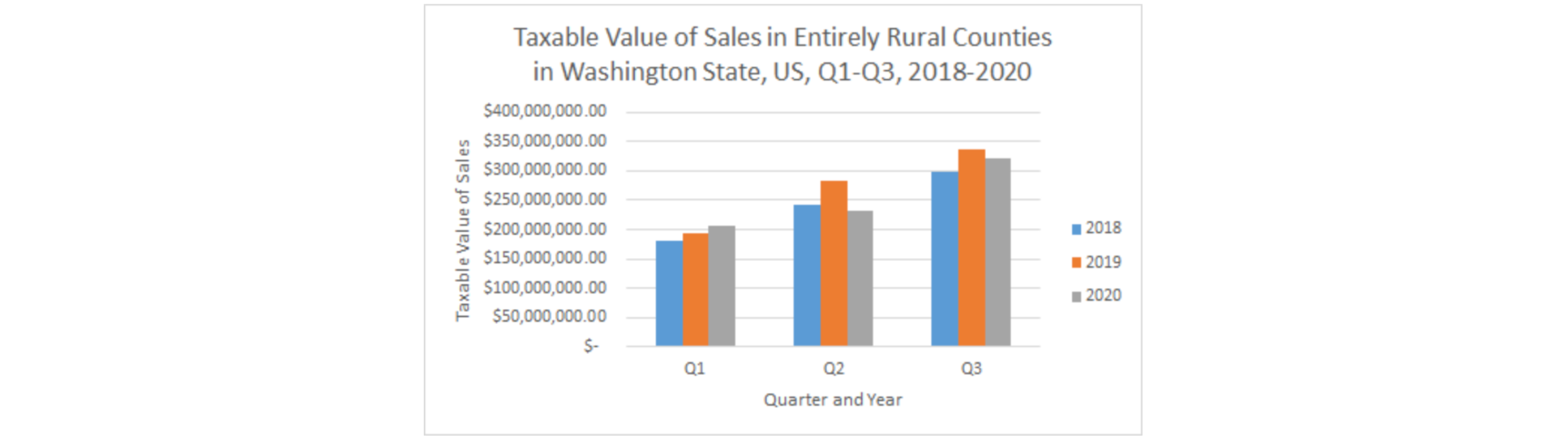

So how have changes in sales taxes varied between urban and rural counties? The US Census Bureau has a useful

So how have changes in sales taxes varied between urban and rural counties? The US Census Bureau has a useful

Nicole is an active community member of Inspire church and the local food bank of Marblemount. She dedicates every Wednesday to helping her community receive food resources by checking in members, setting up for distribution, and making sure things run smoothly.

Nicole is an active community member of Inspire church and the local food bank of Marblemount. She dedicates every Wednesday to helping her community receive food resources by checking in members, setting up for distribution, and making sure things run smoothly. Final Thoughts

Final Thoughts

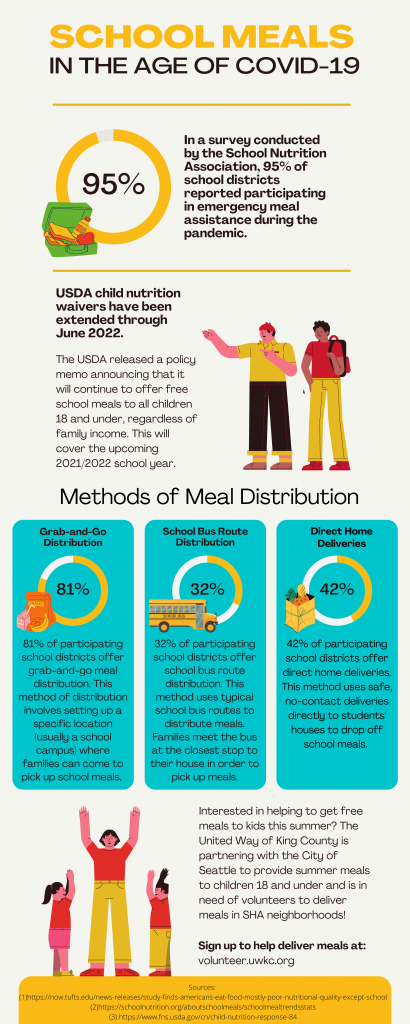

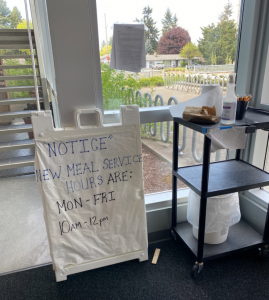

School closures at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic presented school districts with a unique dilemma: how to get school meals to children when they can’t physically attend school. According to the USDA, schools were responsible for feeding over

School closures at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic presented school districts with a unique dilemma: how to get school meals to children when they can’t physically attend school. According to the USDA, schools were responsible for feeding over

“I first made a connection with where my food came from while spending time in the garden with grandfather. He built a miniature greenhouse in his backyard in Florence, Oregon, and allowed my sisters and me to help grow tomato plants. To this day, the smell of your hands after picking tomatoes and the juicy and slightly sweet taste of the tomato flesh reminds me of family.

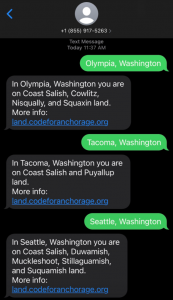

“I first made a connection with where my food came from while spending time in the garden with grandfather. He built a miniature greenhouse in his backyard in Florence, Oregon, and allowed my sisters and me to help grow tomato plants. To this day, the smell of your hands after picking tomatoes and the juicy and slightly sweet taste of the tomato flesh reminds me of family.  Learn more about the Indigenous land you are living on:

Learn more about the Indigenous land you are living on:

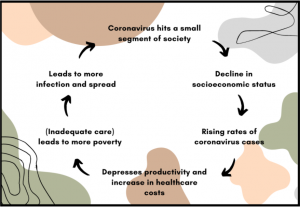

1. Occupation

1. Occupation  2. Inadequate Access to Healthcare

2. Inadequate Access to Healthcare  3. Housing Conditions/Location

3. Housing Conditions/Location  Food Apartheid

Food Apartheid  4. Pre-existing Health Conditions

4. Pre-existing Health Conditions

To say we are proud and honored to work with this inspirational group of youth is an understatement. When the pandemic hit, these individuals could have easily sat back and went forth with their studies, professions, or family lives. But instead, they heeded the call to take action and make a difference.

To say we are proud and honored to work with this inspirational group of youth is an understatement. When the pandemic hit, these individuals could have easily sat back and went forth with their studies, professions, or family lives. But instead, they heeded the call to take action and make a difference.

Do Communicate

Do Communicate Do Explore Positive Coping Skills

Do Explore Positive Coping Skills