COVID-19 has shattered any global sense of stability. It has impacted social interactions, entertainment, travel, business, food service, and education for everyone. As individuals and communities continue to work towards building a new sense of normalcy, education continues to struggle. Teachers are experiencing intense levels of stress and burnout as they attempt to teach virtually, in-person with COVID protocols, or in some cases both at the same time. Students and caregivers are also experiencing unprecedented levels of stress from COVID. As the pandemic wears on without an ending in sight, they are in immediate need of support, resources, and changes in policy.

COVID-19 has shattered any global sense of stability. It has impacted social interactions, entertainment, travel, business, food service, and education for everyone. As individuals and communities continue to work towards building a new sense of normalcy, education continues to struggle. Teachers are experiencing intense levels of stress and burnout as they attempt to teach virtually, in-person with COVID protocols, or in some cases both at the same time. Students and caregivers are also experiencing unprecedented levels of stress from COVID. As the pandemic wears on without an ending in sight, they are in immediate need of support, resources, and changes in policy.

Limited Access to Services

Before COVID, *Antonio was an honor student in his eighth-grade classes. He is currently struggling to maintain a C average as a virtual student. He reads the paragraph on the laptop for the fifth time, squinting and rubbing his temples. He has a headache, which has become a frequent occurrence for him since starting virtual learning. He also reports heightened anxiety from the 5-7 hours a day he is expected to spend in zoom meetings and assignments. Antonio isn’t alone, with nearly half of American children reporting increases in headaches, anxiety, exhaustion, and stress levels related to education in the pandemic.

*Jaylyn is a fourth-grader and has an IEP for his anxiety and ADHD symptoms. During in-person education, Jaylyn has in-class support from a special-education classroom aide. He takes scheduled breaks during the school day and utilizes fidget tools and sensory activities to help manage his stress levels. COVID has changed his routine dramatically. During virtual learning, Jaylyn does not have access to the same support. He has had to learn to cope with noise and movement of other household members and pets while he tries to work. Frustrated after getting an answer wrong, he melts onto the floor and sobs angrily. “I can’t do it! I’m stupid! I hate school!” His outburst will pass, with support from his caregiver, but all students do not have an adult who is able to be home with them during the day. As many as 70% of the workforce is unable to work from home, and for People of Color that climbs as high as 81%. Of adults who are able to stay home, many lack the skills to help with homework assignments or social-emotional concerns. Jaylyn is overwhelmed, anxious, and desperate for a sense of normalcy. His irritability and low self-esteem are frequent symptoms for students who struggle with anxiety or other mental health or developmental concerns.

*Jaylyn is a fourth-grader and has an IEP for his anxiety and ADHD symptoms. During in-person education, Jaylyn has in-class support from a special-education classroom aide. He takes scheduled breaks during the school day and utilizes fidget tools and sensory activities to help manage his stress levels. COVID has changed his routine dramatically. During virtual learning, Jaylyn does not have access to the same support. He has had to learn to cope with noise and movement of other household members and pets while he tries to work. Frustrated after getting an answer wrong, he melts onto the floor and sobs angrily. “I can’t do it! I’m stupid! I hate school!” His outburst will pass, with support from his caregiver, but all students do not have an adult who is able to be home with them during the day. As many as 70% of the workforce is unable to work from home, and for People of Color that climbs as high as 81%. Of adults who are able to stay home, many lack the skills to help with homework assignments or social-emotional concerns. Jaylyn is overwhelmed, anxious, and desperate for a sense of normalcy. His irritability and low self-esteem are frequent symptoms for students who struggle with anxiety or other mental health or developmental concerns.

This is a typical school day for Jaylyn and so many other children. Despite the need for interventions, support from schools has been limited for students with special needs. Balancing safety and the needs of students can be challenging, and those disabilities add additional concerns. For children like Jaylyn with ADHD, focusing on a computer for extended periods of time pushes him to his limit. In addition to symptoms of disabilities, digital concerns have also impacted the special education population at a high rate. Students from low-income families are more likely to be labeled as Special Education by their school systems. Low-income households are less likely to have access to technology or reliable internet, making it even harder for students and caregivers to get the support they need.

The Digital Divide

When most American schools shuttered their doors in March 2020, a large number of them were grossly unprepared for the lasting impact that the COVID-19 pandemic would have on the educational process. The largest concern that emerged was the lack of reliable technology and internet services for students to use while sheltering at home. Low-income and rural families have experienced the most intense effects of this gap in equity, and Students of Color have been hit hardest of all. 4.4 million U.S. households with over 11 million students lack access to a computer necessary for virtual learning. Some school districts have gotten creative with their efforts to address the lack of internet through unconventional ways like parking wifi-enabled school buses in neighborhoods. Further support and innovative ideas like this are needed to help students succeed.

Students who are fortunate enough to have internet access are still burdened with other concerns. Low internet speeds often hurt participation in zoom calls and other forms of video meetings with teachers. 59% of low-income students report technology-related difficulties when trying to participate in virtual learning. This has led to missing instruction, assignments, and increases in attendance issues. Black and Brown children are 50% less likely to have access to live sessions with their teachers during virtual learning at all. This has impacted grades, test performances, and has created an additional barrier to students being able to ask questions or gain clarity on assignments. COVID has widened the already substantial achievement gap between predominately white schools and schools where Students of Color are the majority. White students have experienced an estimated 7 months of lost academic growth since COVID, while Black and Brown students are testing an average of 10 months lost growth. How will students recover? This question remains largely unanswered.

Inequity in Funding

Inadequate equipment, resources, and lack of staff support often boil down to a lack of financial resources. Schools, where the majority of students are People of Color, receive an average of $2,226 less per student, per year than schools where their students are predominately white. This means less money for staffing, repairs, equipment, technology, student support services, and safety protocols that are necessary to operate safely during a pandemic. U.S. schools are intensely segregated and receive 35% of their funding from local tax dollars. This means that students from low-income communities have access to fewer resources and lower quality education. It also means that these students have less exposure to diversity, inclusion, and multiculturalism. Children who lack experiences with people who are different from them racially, socioeconomically, or culturally, are more likely to leave school lacking the skills needed to fully integrate into society. The negative effects of segregation often follow them for the rest of their lives.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Increase Funding

Increasing funding in low-income school districts will even the playing field. It will allow for school districts to expand learning opportunities and the time provided to students for instruction and assignment completion. This gives students more chances to regain information and progress damaged by the pandemic. Increased funding will also allow for expanded hiring of teachers, classroom aides, and after-school tutors. More trained adults in the in-person or online classroom mean a lower teacher-student ratio. This gives students the opportunity to benefit from individualized learning plans and interactions. Funding increases will also allow for desperately needed creation and expansion of school-based mental health services. COVID has brought a great deal of stress and change for students and providing a safe, trusted, professional to support students’ mental health has never been more critical than it is today.

Reimagine School Systems

The U.S. education system is still highly segregated, which negatively impacts learning outcomes for students. School systems, their boundaries, and their designs need to be reimagined. Gerrymandering and single-family residential zoning have hurt public education and limited diversity and equity in schools. Ending this system and implementing federal standards for diversity will hold school districts accountable for their inclusive practices. These standards should leave room for local communities to implement their own ideas about best-methods for diversifying student-bodies and staff. Allowing local input, while still promoting accountability, prioritizes the empowerment of stakeholders such as local leadership, teachers, households, and students.

Hold Policy-Makers Accountable

Elected officials at local, state, and federal levels hold extensive power in upholding the current system or making needed changes. Involvement in local opportunities to engage with policy-makers such as school boards or elected officials is critical to supporting equity in education. You can find the names and contact information for your representatives here if you would like to express concerns, support, or suggestions for making changes in education in your community or nationwide.

Support Changemakers

There are numerous organizations that have dedicated their time, energy, and resources to supporting educational equity. They have passion and a mission for change, but they cannot succeed alone. They need support from individuals just like you who want to see positive changes and raise awareness and support for their causes. For more information on ways you can contribute please visit equityineducation.carrd.co.

Sylvia Rivera

Sylvia Rivera Marsha P. Johnson

Marsha P. Johnson

It has now been over 50 years since the Stonewall Rebellion and still, our

It has now been over 50 years since the Stonewall Rebellion and still, our

Valentine’s Day, arguably the most romantic holiday of the year, is fast approaching. As you prepare to share this day with your loved ones, take a moment to reflect on what being in a loving healthy relationship means to you. For some people, especially our youth, being in a relationship may be a completely new phenomenon. Join us in educating our youth on healthy relationship building as we increase awareness for intimate partner violence in teen dating and prepare for a future with less violence.

Valentine’s Day, arguably the most romantic holiday of the year, is fast approaching. As you prepare to share this day with your loved ones, take a moment to reflect on what being in a loving healthy relationship means to you. For some people, especially our youth, being in a relationship may be a completely new phenomenon. Join us in educating our youth on healthy relationship building as we increase awareness for intimate partner violence in teen dating and prepare for a future with less violence. Take Action

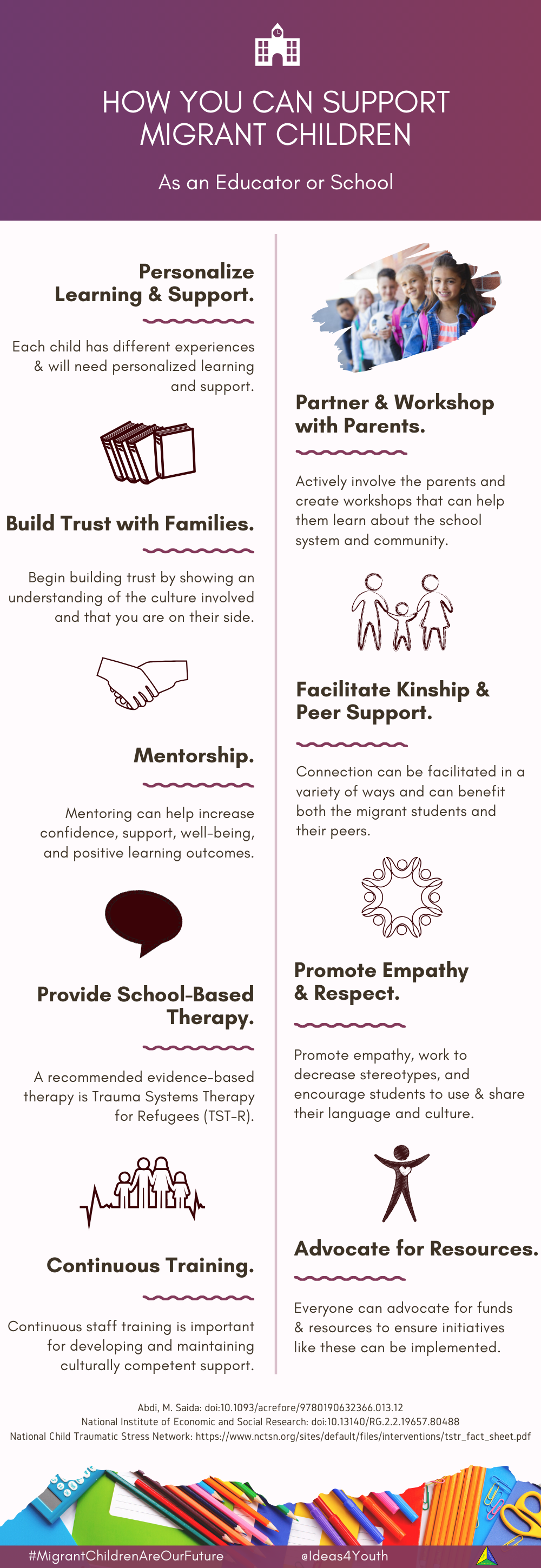

Take Action Schools play an important role in supporting migrant children as they integrate into their communities or navigate the challenges of growing up as children of migrant parents. Educators can provide a place for migrant children to feel safe, learn about their community, build friendships and connections, and discover their innate strengths. Schools can support parents through active inclusion, workshops, events, and other engagement opportunities. While these undertakings can seem daunting, this blog will provide ways that schools and educators can begin creating supportive, trauma-informed environments for migrant children and their families.

Schools play an important role in supporting migrant children as they integrate into their communities or navigate the challenges of growing up as children of migrant parents. Educators can provide a place for migrant children to feel safe, learn about their community, build friendships and connections, and discover their innate strengths. Schools can support parents through active inclusion, workshops, events, and other engagement opportunities. While these undertakings can seem daunting, this blog will provide ways that schools and educators can begin creating supportive, trauma-informed environments for migrant children and their families. In addition to focusing on the child, actively involving the parents is crucial to a student’s academic success. For recent arrivals, parenting in a new country can be confusing with unfamiliar school systems, norms, policies, values, and expectations. Educators can play an important role in a family’s integration into the community, benefiting both the parents and the students. To do so, extend an inclusive and welcoming atmosphere to the parents or guardians from the very beginning. Translate all documents, events, and communications. Create school-based workshops that incorporate things like English language and literacy development, information about the U.S. school system, how they can best support their children in school, their rights as members of the community, and how to access healthcare and other important services.

In addition to focusing on the child, actively involving the parents is crucial to a student’s academic success. For recent arrivals, parenting in a new country can be confusing with unfamiliar school systems, norms, policies, values, and expectations. Educators can play an important role in a family’s integration into the community, benefiting both the parents and the students. To do so, extend an inclusive and welcoming atmosphere to the parents or guardians from the very beginning. Translate all documents, events, and communications. Create school-based workshops that incorporate things like English language and literacy development, information about the U.S. school system, how they can best support their children in school, their rights as members of the community, and how to access healthcare and other important services.  As students navigate the school environment, their peers can play a significant role in their progress and successful integration. Facilitate friendship and peer support through activities such as buddy systems, peer-to-peer language learning, and extra-curricular activities.

As students navigate the school environment, their peers can play a significant role in their progress and successful integration. Facilitate friendship and peer support through activities such as buddy systems, peer-to-peer language learning, and extra-curricular activities.  With the understanding of migrant children’s unique experiences comes a responsibility to promote empathy and respect towards them and their families. Challenge the acceptance of any negative stereotypes that you come across both inside and outside of the classroom. Show respect for their culture and language; convey that it is valuable to retain and not just something to be replaced.

With the understanding of migrant children’s unique experiences comes a responsibility to promote empathy and respect towards them and their families. Challenge the acceptance of any negative stereotypes that you come across both inside and outside of the classroom. Show respect for their culture and language; convey that it is valuable to retain and not just something to be replaced.

One of the simplest things that you can do is listen, support, and encourage. Children who have faced a lot of trauma often just need someone to listen. Be a friend, and

One of the simplest things that you can do is listen, support, and encourage. Children who have faced a lot of trauma often just need someone to listen. Be a friend, and  Unaccompanied minors that arrive in the country may have no one to take care of them and can end up in shelters or the foster care system. Even children who have relatives in the country may never live with them because many families fear that if they come forward to claim the child they will be deported. Additionally, children whose parents are suddenly deported

Unaccompanied minors that arrive in the country may have no one to take care of them and can end up in shelters or the foster care system. Even children who have relatives in the country may never live with them because many families fear that if they come forward to claim the child they will be deported. Additionally, children whose parents are suddenly deported

How Schools Can Increase Protective Factors

How Schools Can Increase Protective Factors School Climate, Community-Building and Beyond

School Climate, Community-Building and Beyond

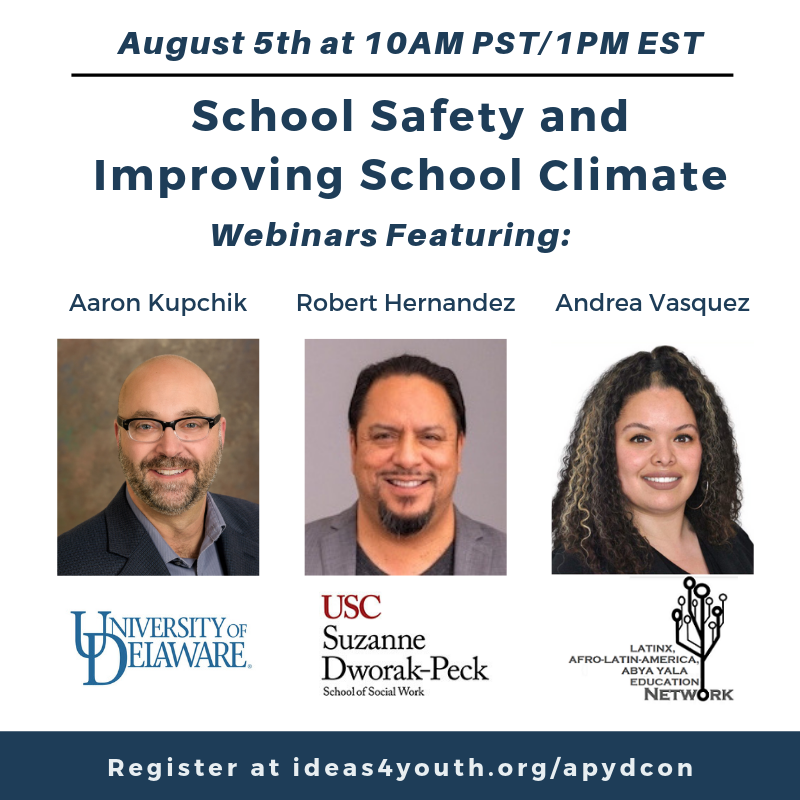

These children are our future. Everyone from community members to professionals to educators can help. Join us for our Alliance for Positive Youth Development Best Practices for Youth Conferences on August 5-7, as we discuss this issue further and learn best practices for supporting refugee and migrant children. The second day of workshops is devoted to this topic and includes an expert Q&A panel featuring Bhairavi Asher, Children’s Representation Project Managing Attorney at ImmDef, and Nicolas Hernandez, Organizing Director at RAICES Texas. Following this will be a presentation by Sarah Kim Pak, UCLA Public Service Fellow at the National Immigration Law Center. Register for free at

These children are our future. Everyone from community members to professionals to educators can help. Join us for our Alliance for Positive Youth Development Best Practices for Youth Conferences on August 5-7, as we discuss this issue further and learn best practices for supporting refugee and migrant children. The second day of workshops is devoted to this topic and includes an expert Q&A panel featuring Bhairavi Asher, Children’s Representation Project Managing Attorney at ImmDef, and Nicolas Hernandez, Organizing Director at RAICES Texas. Following this will be a presentation by Sarah Kim Pak, UCLA Public Service Fellow at the National Immigration Law Center. Register for free at

An appropriate response to school safety and violence prevention should come from the consideration of big-picture thinking, systems analysis, and bio-psycho-social analysis. As a social worker, I advocate for looking at problems from a “systems” approach so that we can create effective and holistic solutions. This often requires redefining the “problem.” While school violence has been on the rise,

An appropriate response to school safety and violence prevention should come from the consideration of big-picture thinking, systems analysis, and bio-psycho-social analysis. As a social worker, I advocate for looking at problems from a “systems” approach so that we can create effective and holistic solutions. This often requires redefining the “problem.” While school violence has been on the rise,