Money allocated for mental health services and social entrepreneurship support in Dadaab could help refugees build a future outside the camp

Last week, Rebecca posted the second entry of our series on the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya. Much of her post focused on the monetary difficulties related to the camp. She explained how there is a funding shortage of approximately $800 million in relation to the drought and famine in the Horn of Africa. Towards the end of her post, she raised a very important question: Is the money that is available being put to the best possible use?

While it is obviously important to take care of basic needs like food, water and medical care, other services are needed in order to enable refugees to eventually leave the camp. I want to expand on mental health care, a service we’ve already mentioned, and social entrepreneurship, a service we have not yet discussed. These are two critical elements of a successful refugee camp that are not being given enough focus at Dadaab.

If you think about it for a minute and imagine the situations in which these refugees are arriving at Dadaab, it’s easy to understand why mental health is a large cause for concern. A 2003 study of Somali refugees in Uganda discovered that over 70% of those surveyed had witnessed dead or mutilated bodies and that just under 70% had experienced a shelling or bomb attack. While this study doesn’t directly apply to the Somali refugees currently at Dadaab, the fact that the violent situation in Somalia has only worsened since 2003 allows us to assume similar statistics for the refugees of 2011.

And then you must factor in the stressors of journeying from one’s homeland to a distant, massively overcrowded camp. Travelling refugees are easy targets for bandits, who may take the few provisions and possessions the refugees were travelling with. Some families, pregnant mothers and all, have walked for 30 days with hardly any nourishment. Upon arrival to the camp, they are greeted with incredibly long lines outside the camp (in my last post I mentioned how some are waiting 12 days just to start receiving food rations). That’s a 12-day wait on top of a 30-day journey – a month and a half of struggling just to stay alive.

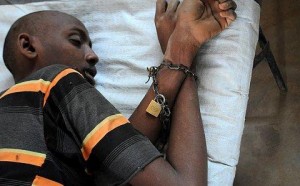

As I said, it’s not hard to imagine where mental health issues are stemming from. Arduous situations as those that I described above can easily lead to post-traumatic stress disorder. In order to keep those suffering from post-traumatic stress from harming themselves or others, families will often chain together the hands of unstable family members. While this may hinder the damage an unstable person may do and offer a temporary fix, it is inhumane and not at all a solution. Fortunately, some limited counseling services are available. The hospital run by Doctors Without Borders in Dadaab allows for some patients to be seen by a small team of clinical psychologists. Similarly, a team of counselors from CARE International, an organization responsible for much of the aid given at Dadaab, offers counseling services to refugees. CARE has found that a number of refugees are reluctant to speak openly with their friends and relatives about their personal issues for fear of being stigmatized.

harming themselves or others, families will often chain together the hands of unstable family members. While this may hinder the damage an unstable person may do and offer a temporary fix, it is inhumane and not at all a solution. Fortunately, some limited counseling services are available. The hospital run by Doctors Without Borders in Dadaab allows for some patients to be seen by a small team of clinical psychologists. Similarly, a team of counselors from CARE International, an organization responsible for much of the aid given at Dadaab, offers counseling services to refugees. CARE has found that a number of refugees are reluctant to speak openly with their friends and relatives about their personal issues for fear of being stigmatized.

But these services are not reaching nearly enough of the 400,000+ residents of Dadaab. Isoe-Nyachieng, a psychologist with Doctors Without Borders, put it this way, “Mental health has not been given the emphasis it deserves. If all can be given the same coverage, like nutrition and malaria or HIV/AIDS…If mental health can be given that level then we’ll be able to manage our patients very well.” Mental health must become a higher priority at Dadaab.

The second service I’ll briefly discuss is that of social entrepreneurship in refugee camps. Unlike mental health services, I have found no evidence of plans to encourage social entrepreneurship in Dadaab. That’s not to say there are no such plans; I’m simply saying I found none that are widely discussed or published. The basic benefit of this endeavor is to assist refugees in building a sustainable lifestyle – something that would allow them to flourish while in the camp, create opportunities for other refugees to flourish and eventually export their services outside of the camp and into the wider community. Basically, it’s about helping the refugees start small businesses within the camps that can create sustainable social change.

This is somewhat different from general entrepreneurship in which profit is the main concern. By putting an emphasis on supporting the social aspect, a wider benefit to the camp can be realized. This might mean encouraging businesses to grow and hire other refugees to help more than just the business owner out of poverty. With enough refugees working, true social change could happen. “Social entrepreneurship projects are important in reducing refugees’ dependency on foreign aid and their ability to promote sustainable living.”

One real life example of the benefits of social entrepreneurship comes from Kakuma refugee camp in Northwest Kenya. Somali refugees there started a microcredit system to aid groups of women in establishing businesses. Once one business was established, money was loaned to another group, creating one sustainable enterprise after another. These businesses can be as simple as a rudimentary bakery that bakes only two or three types of bread. Somali leaders in the camp claimed that almost 90% of Somalis in the camp no longer relied on UN aid after the establishment of this program. Not only is this an excellent example of social entrepreneurship, it’s a great demonstration of the importance of supporting women in refugee camps. This helps ensure that it is not only the refugee men who are provided with an opportunity to get back to their feet.

If a portion of the aid money at Dadaab was set aside to help implement a microfinance system that offered small loans to refugees with business plans that could work towards social change , the cycle of poverty within the camp might eventually be broken. Combining this plan with increased mental health services would go a long way in assisting refugees in building their own sustainable futures.

Detailed plans such as this one require the cooperation of donors, aid organizations and camp officials. When these groups fail to agree on the best way to aid refugees, it is the residents of the camp who suffer. In the fourth and final post of this series, Rebecca will examine this potential disconnect and see if there’s any way in which it can be eliminated. Stay tuned.

Ryan Pavel is a Program and Research Intern with the SISGI Group focusing on foreign military involvement, policy and strategy into conflicts and motivations behind and impact of foreign aid. To learn more about the SISGI Group visit www.sisgigroup.org