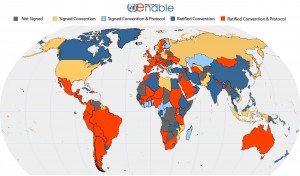

In my earlier post I offered some background information about the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), including its history and purpose. I wrote the piece in recognition of the 100th ratification of the treaty last week, but it’s important to understand that ratifying is simply the first step. The hard work begins after ratification, when countries have to demonstrate to the international community a genuine commitment to the goals of the treaty. In order for a treaty to be effective, countries must show sustained progress in implementing and monitoring the core principles of the CRPD, which include:

1) Respect for Inherent Dignity

2) Non-discrimination

3) Full inclusion in society

4) Respect for difference, and the acceptance of Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) as part of human diversity

5) Equality of Opportunity

6) Accessibility

7) Equality between men and women

8) Respect for the evolving capacities of children with disabilities, and their right to preserve their identities.

The twelve-member Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is charged with the task of monitoring each country’s performance with respect to the principles above. The committee works within the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, which oversees all “human rights”-related treaties and activities throughout the UN system, and has the power to address on-going, widespread human rights abuses. Every four years countries that have ratified the CRPD are required to submit progress reports, detailing steps they’ve taken to support legislative, judicial, and policy changes in accordance with the CRPD’s objectives. Examples might include increasing political participation by establishing a quota for the number of PWDs working in the government, or redesigning federal income support programs so that they take the financial needs of PWDs into account.

above. The committee works within the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, which oversees all “human rights”-related treaties and activities throughout the UN system, and has the power to address on-going, widespread human rights abuses. Every four years countries that have ratified the CRPD are required to submit progress reports, detailing steps they’ve taken to support legislative, judicial, and policy changes in accordance with the CRPD’s objectives. Examples might include increasing political participation by establishing a quota for the number of PWDs working in the government, or redesigning federal income support programs so that they take the financial needs of PWDs into account.

Although country reports are extremely helpful for monitoring purposes, the Committee can do nothing more than offer recommendations – it has no power to enforce the CRPD. Enforcement is left entirely up to national governments, and, as we have seen among notorious human rights violators like China, Saudi Arabia, Cuba, Russia, and Pakistan, membership to a human rights treaty does not guarantee that a country will live up to its promise. Of course, NGOs, grassroots organizations, and Disabled Persons Organizations (DPOs) can play a very important role in disseminating information to educate the population and lobby for disability rights. But if societal attitudes towards disabilities are so prevalent and rigid that PWDs are physically prevented from organizing, DPOs and NGOs are out of the question.

So, then, we come to my main question: How far can the CRPD reach, when governments put token policies and laws in place, but fail to enforce them or change negligent attitudes towards PWDs? As a recent example from Human Rights Watch shows, women with disabilities in northern Uganda are more vulnerable to poverty and sexual violence. This isn’t because the appropriate laws aren’t in place; Ugandan laws prohibit discrimination against PWDs. Instead the violence is exacerbated by local and regional attitudes towards PWDs, especially women. Not only are women with disabilities more likely to be shunned by communities, but in this case their perceived vulnerability is exploited by men for sex.

Some might say that without adequate law enforcement, violence and exploitation are bound to go unchecked in any society. But I disagree. If it takes a policeman on every corner to prevent the acceptable abuse and marginalization of PWDs, then there is something inherently missing in the ethical code of the culture. I used northern Uganda as an example, but this applies to every society on some level. If all members of a population can’t incorporate the rights of PWDs into their norms, what hope do we have that they will police their own actions when the policeman is no longer there? It’s not enough to make laws, quotas, provisions, accessibility requirements, etc, if people aren’t expected to uphold the principles of inclusion in their own daily actions and activities. It’s not enough to put aside special accommodations, when a majority of the population isn’t educated about the humanity and value of PWDs. The CRPD, like all conventions, is an excellent document that standardizes ideas about inclusion, equality, and human rights. But there is still a logistical gap between the distant, idealistic principles put forth by the UN, and the realities of local attitudes and misunderstandings – which only education can fix. This can be in the form of formal education that includes children with disabilities, or national campaigns to raise awareness about PWDs. Whichever the method, without educating the public to change discriminatory attitudes, laws will carry no weight.

Sarah Amin is a Program and Research Intern with the SISGI Group’s Research Division focusing on Human Rights Advocacy, International Disability Rights and Gender Equality/Gender Mainstreaming. To learn more about the SISGI Group visit www.sisgigroup.org.