“As your school counselor, your safety is my first priority.” I cannot count how many times I have said that phrase to students, and I’m pretty good at counting. It was usually one of the first things I said as part of a quick, limits-of-confidentiality spiel, and it helped set the tone for what students could expect of me. In a political climate that has legislators refusing to take evidence-based steps to help reduce school shootings, in the very presence of school shooting victims, student safety remains an urgently relevant concern. When reading the phrase, “student safety,” the physical, bodily safety of students may immediately come to mind. Less likely to be considered, but still very worthy of attention is our students’ emotional safety.

Before we get into an examination of emotional safety in the classroom, let’s talk about the brain’s limbic system. The limbic system manages survival behaviors and emotional responses. The amygdala, which is part of the limbic system, connects emotions to our memories (if you’re familiar with the Disney Pixar film, Inside Out, Headquarters is kind of like the amygdala). The amygdala also initiates the fight, flight, or freeze response. Here’s how that response works. You encounter what your amygdala perceives to be a threat. The amygdala sends signals to your body to release adrenaline and cortisol, to help prepare you to either confront the threat, or flee from the threat. Sometimes, if a threat is perceived to be particularly intense, the body will prepare to fight or fly, but instead of “fighting” or “flying”, the body freezes. The frequent release of adrenaline and cortisol short-circuits the parts of the brain that have to do with learning and self-regulation. We call this collective response to threat, stress.

Before we get into an examination of emotional safety in the classroom, let’s talk about the brain’s limbic system. The limbic system manages survival behaviors and emotional responses. The amygdala, which is part of the limbic system, connects emotions to our memories (if you’re familiar with the Disney Pixar film, Inside Out, Headquarters is kind of like the amygdala). The amygdala also initiates the fight, flight, or freeze response. Here’s how that response works. You encounter what your amygdala perceives to be a threat. The amygdala sends signals to your body to release adrenaline and cortisol, to help prepare you to either confront the threat, or flee from the threat. Sometimes, if a threat is perceived to be particularly intense, the body will prepare to fight or fly, but instead of “fighting” or “flying”, the body freezes. The frequent release of adrenaline and cortisol short-circuits the parts of the brain that have to do with learning and self-regulation. We call this collective response to threat, stress.

Now, back to emotional safety in schools. According to the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, emotional safety is, “[an] experience in which one feels safe to express emotions, security, and confidence to take risks and feel challenged and excited to try something new.” Put another way; an emotionally-safe environment is one in which failure, or the potential for failure, are not perceived as threats. If you have ever been in a classroom as a student, unfortunately, you are probably familiar with the concept of an emotionally-unsafe setting. Many remember their years in middle and high school to be especially fraught with self-consciousness and worry, full of potential emotional threats at every turn.

The Fight-Flight-or-Freeze Response in the Classroom

As an educator, I have seen students respond to perceived emotional threats in the classroom, for example, being called on to answer a question or having to take a test, by:

- “Fighting” – becoming angry and defiant

- “Flying” – not doing their work, trying to get kicked out of class, and

- “Freezing” – shutting down, not engaging

Educators sometimes write-off students who react these ways in class, but it’s important to recognize that such students have often already been exposed to other, more threatening stressors at home, or in the community. It’s no coincidence that schools that report higher-than-average discipline rates also happen to be in the poorest neighborhoods, which also happen to be populated primarily with families from minoritized groups. Students from such socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds are often dealing with trauma histories that have put them into a constant state of stress. As we know, that stress hijacks their learning. But when a school is emotionally-safe, students with trauma histories feel secure enough “to take risks and feel challenged and excited to try something new.”

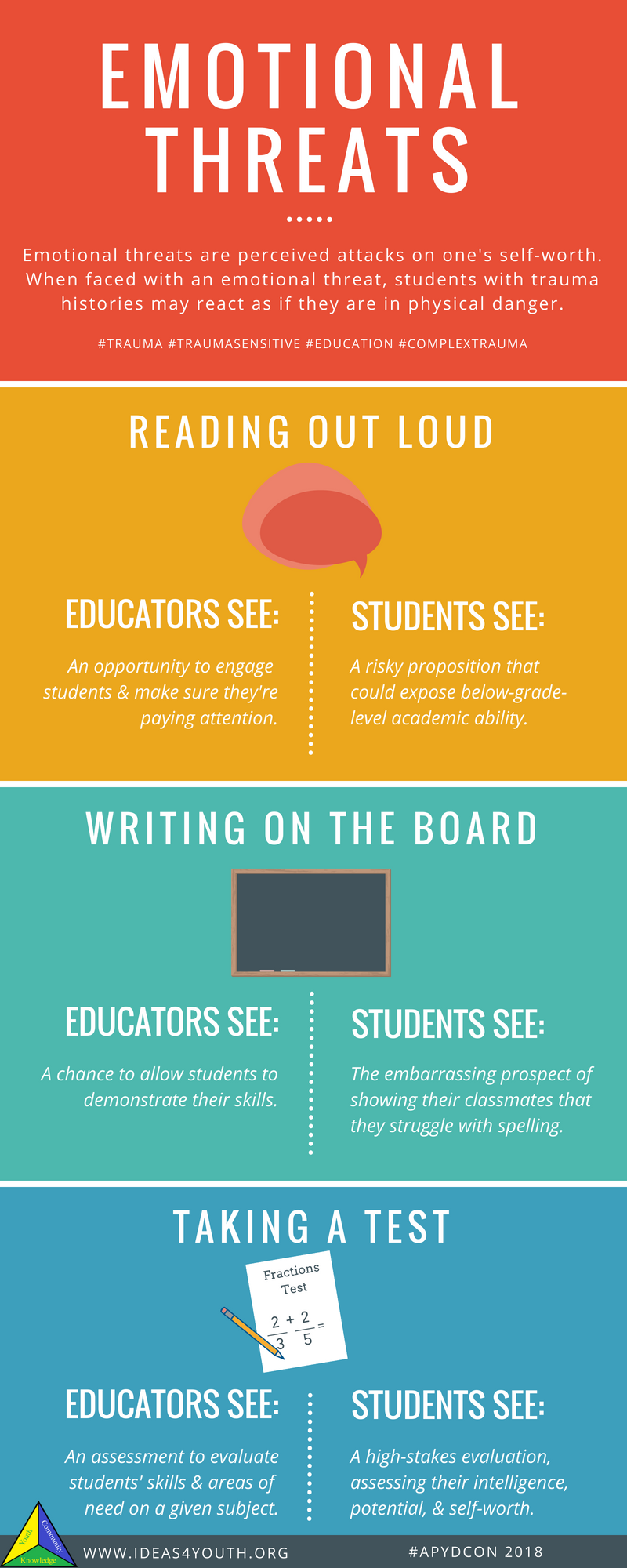

The following infographic shows why students with trauma histories may “act out” when asked to participate in seemingly simple classroom activities.

Ready to Learn More?

On August 6th, 2018, the Alliance for Positive Youth Development is having FREE online workshops on Trauma-Sensitive Education at this year’s APYDCON. The first workshop will be a panel Q&A with experts Anna Paravono-Frise, an educator and advocate of youth trauma, and Towana Cately, a counselor at Antelope Valley College. The day will end with a presentation by Anne-Marie Gauto, a professor at the University of Southern California Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. The panel and presentation will address best practices for identifying and supporting students with trauma histories. Visit ideas4youth.org/apydcon to register.