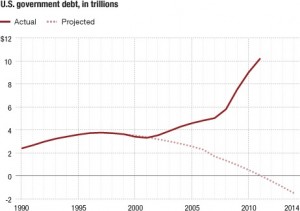

Just over a decade ago, public debt was just under $3 trillion and the US was running a budget surplus. Two wars, two recessions, and eleven years later, the debt has skyrocketed to $14.94 trillion, $10.20 trillion of which is public debt (debt held by investors outside the federal government, the Fed, foreign, state, and local governments). Today, economists wonder how the US government will be able to pay off its debt. David Kestenbaum of NPR recently wrote an article discussing a fear that economists within the Clinton administration had – that the US would eventually pay off all of its debt and would stop issuing US Treasury bonds.

It might be hard to believe now, but this was actually a valid concern during the Clinton administration. The CBO projected that the national debt would be paid off by 2012. Kestenbaum acquired a government report via the Freedom of Information Act Request titled “Life After Debt,” in which economist Jason Selgiman voiced his concern that this reduction in Federal debt and eventual accumulation of Federal asset presents three big issues:

Kestenbaum acquired a government report via the Freedom of Information Act Request titled “Life After Debt,” in which economist Jason Selgiman voiced his concern that this reduction in Federal debt and eventual accumulation of Federal asset presents three big issues:

1) Investors could no longer capitalize on risk free and easily attainable US Treasury bonds, and these bonds would no longer serve as a benchmark to compare the returns of other, riskier investments to or set mortgage rates.

2) The Fed would have to change the way it conducts monetary policy. Currently, the Fed’s conducts open market operations to influence bank reserves, short-term interest rates, and money supply by buying and selling Treasury bonds. As the government paid off its debt and the Fed no longer held Treasury bonds, they would have to conduct open market operations buy buying and selling corporate bonds, agency debt, and sovereign debt. Whichever assets the demand for Treasury bonds shifts to will become the new benchmark for interest rates around the world. However, Selgiman discussed his concerns this might be risky, as investors might not be as confident in these new assets as they were in Treasury bonds.

3) After the government pays off its debt, what will they do with their continued surplus? They could buy state and local bonds, but historically these bonds have much lower returns than Treasury bonds. Also, just as foreign countries and investors would no longer be able to invest in Treasury bonds, money for Social Security could no longer be invested in Treasury bonds. Whereas purchasing sovereign debt has guaranteed returns, many other investments do not have this guarantee. With both the US surplus and Social Security funds, the government would have to decide which assets to invest in that would mitigate risk and also have decent returns.

Seligmen and other economists in the Clinton administration assessed the risks and decided in the long run, while paying off some of its debt as quickly as possible would be beneficial and decrease interest expenses, it would not be in America’s best interests to pay off all of its debt. After all, if the government got stuck with a surplus and a lack of risk-free assets to invest in, it may be stuck in a place where it has to cut taxes to an unsustainable level or invest riskily. While tax cuts may be good in the short run, it probably is not a good option because the government will probably have to raise its revenue stream in the future. This will add uncertainty to the market. Because there isn’t necessarily a good place for this surplus to go, the Fed would not have the ability to precisely control monetary policy, and foreign investors, governments, and banks would have no risk-free asset to invest in, it is probably best for the US to have some outstanding debt.

This is not to say that economists in the Clinton administration would advocate the government’s excessive spending over the past decade. Due to business cycles, there are often times (such as the recent Great Recession) where the government has no choice but to increase spending to inject money into and stimulate the economy. Having too large of a debt makes it difficult to incur more and more debt while maintaining good standing in the credit market. The US government found this out the hard way this August, when Standard & Poor downgraded the US sovereign credit rating from AAA to AA+. Many economists would agree that it is important for a country to find a good balance between too much and too little debt.

Unlike a lot of the news that I see and read these days, most of this article was backed up by actual official reports. Every day, all over my Facebook and Twitter profiles, I see links to articles with clear agendas. From blatantly pro and anti OWS articles to blatantly pro and anti Tea Party articles, I do not see the balance and objectivity out of news outlets that they proclaim to portray. I think a lot of this is because of the rise of social media networks. News sites strive on webpage clicks, and it certainly seems more interesting to vilify or laud someone controversial. Social media users are captivated by these intriguing headlines and editorialize them even more before they share them with their friends and followers. And as a result, we choose what to believe based on biased mainstream sources rather than what is actually going on.

My concern is that as a result of over-reporting sensational stories and extreme opinions, we often ignore discussing these types of issues that Kestenbaum brings up. Public debt isn’t always the worst thing ever, and spending cuts aren’t always the worst thing ever either. The article that I discuss above is just one example of unbiased reporting from NPR. A source such as this, which does not rely on maximizing profits as do mainstream media sources, can be more reliable. While many media outlets have shifted from reporting policy analysis and implications to focusing all their time on reporting sex scandals and Kardashian weddings, NPR does a better job reporting actual stories that matter. Sources for good news and analysis do exist. Unfortunately, people cannot rely solely on mainstream media outlets and should look to other sources to find unbiased facts. I hope we don’t cut funding for NPR and make it even harder to find these facts.

Shaunak Varma is a Program and Research Intern with the SISGI Group. To learn more about the SISGI Group visit www.sisgigroup.org.