Last spring, I took an ethics class called Policy Choice as Value Conflict. Throughout the semester, we students debated the merits of riveting topics, ranging from pros and cons of moral philosophies such as utilitarianism and deontology to the legality of controversial issues such as capital punishment, euthanasia, prostitution, gay marriage, and even bestiality. Our class comprised of conservatives and liberals, atheists and evangelicals. Each day, we heard every side’s intriguing arguments and rarely reached consensus.

But occasionally, we did find unanimous agreement. One such instance, our professor assigned us to watch “The Ghosts of Abu Ghraib,” a documentary made by filmmaker Rory Kennedy. In her documentary, Kennedy explored the horrific abuse American soldiers inflicted upon Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib. We all agreed. The inhumane treatment that these prisoners received violated international law and was inherently wrong.

In case you don’t know, the Abu Ghraib prison was a notorious prison in Iraq, at which American guards committed various human rights violations upon prisoners, humiliating them by forcing them to be naked, torturing them, mutilating them, raping them, and forcing them to rape each other. After pictures were leaked that documented the torture at Abu Ghraib, the United States Army Criminal Investigation Command performed an investigation that confirmed the wrongdoing by the guards. 11 soldiers were eventually court-martialed and sentenced to military prison.

When I first heard the story about Abu Ghraib and the torture that happened there, I assumed that these guards epitomized evil. That I, nor any other decent human being, would ever have done the same thing had we been in those guards’ shoes. I looked at the photographs in disbelief and wondered how American soldiers could do something so barbaric.

But the film managed to humanize these perpetrators. Kennedy conducted interviews with many of the guards that tortured the prisoners. While they certainly weren’t blameless, they did not seem to be as unimaginably evil or sadistic as you might think. The guards seemed to have been transformed by their environment. As one guard said, Abu Ghraib “turned me into a monster.” Another guard followed up saying “It’s easy to sit back in America or in different countries and say, ‘Oh, I would have never done that,’ but, until you’ve been there, let’s be realistic: You don’t know what you would have done.”

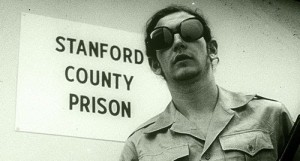

Comments such as these reminded me of an experiment I learned about in a psychology class. In 1971, Stanford University psychology professor Phillip Zimbardo conducted an experiment in which he monitored the psychological effects of becoming a prisoner or prison guard. For the experiment, Zimbardo randomly assigned 24 psychologically healthy subjects roles as guards and prisoners. He set up a mock jail, gave the “guards” wooden batons, and gave both “guards” and “prisoners” appropriate uniforms.

experiment in which he monitored the psychological effects of becoming a prisoner or prison guard. For the experiment, Zimbardo randomly assigned 24 psychologically healthy subjects roles as guards and prisoners. He set up a mock jail, gave the “guards” wooden batons, and gave both “guards” and “prisoners” appropriate uniforms.

During the experiment, the relationship between guards and prisoners became increasingly hostile. Each group internalized their roles and developed solidarity. Early on in the experiment, the prisoners rioted against the guards. The situation quickly escalated. Over the course of the next few days, guards tortured the prisoners by taking away their mattresses and forcing them to sleep on concrete, refusing to allow prisoners to use the bathroom, and even forcing them to strip naked. The chaos that ensued was so bad that Zimbardo had to stop the experiment after 6 days as opposed to the planned 2 weeks because he feared inflicting permanent psychological damage on the subjects.

Recalling this experiment, I wondered if the guards at Abu Ghraib were unique. If psychologically stable subjects in Zimbardo’s experiment managed to commit torture on completely innocent prisoners over the course of six days, it seems pretty unlikely that the Abu Ghraib atrocities are isolated incidents. One account I read by Dave Eshelman, reportedly the most abusive and sadistic guard in Zimbardo’s experiment, was particularly revealing:

When the Abu Ghraib scandal broke, my first reaction was, this is so familiar to me. I knew exactly what was going on. I could picture myself in the middle of that and watching it spin out of control. When you have little or no supervision as to what you’re doing, and no one steps in and says, “Hey, you can’t do this”—things just keep escalating. You think, how can we top what we did yesterday? How do we do something even more outrageous? I felt a deep sense of familiarity with that whole situation.

One thing seems clear from Zimbardo’s experiment and the Abu Ghraib scandal. Power corrupts when allowed to exist unsupervised. Such abuses of power should not be allowed under any circumstance. Thus, prison guards need to be trained to understand the potential dangers of the guard-prisoner relationship. They should also face stringent on-the-ground supervision by an authority figure that ensures that no wrongdoing takes place. Finally, there needs to be transparency between these prisons and the public. We should be able to see pictures and hear reports about what is happening at the prisons. By taking these measures, we can prevent future abuses of human rights similar to what we saw in Abu Ghraib.